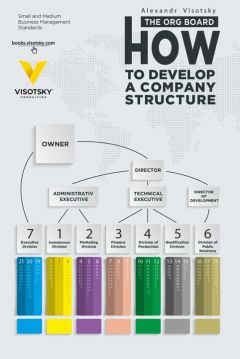

Текст книги "The org board. How to develop a company structure"

Автор книги: Александр Высоцкий

Жанр: Малый бизнес, Бизнес-Книги

Возрастные ограничения: +12

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 17 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 6 страниц]

Chapter 7

Responsibility

There is another important component directly related to the separation of functions – responsibility. Executives often talk about the lack of this substance, so it’s worth taking a better look.

Responsibility is the condition where a person, of their own will or initiative, willingly deals or cares about something. When an employee, faced with difficulties, immediately gives up, or even simply does not do his job, we call it a lack of responsibility. When he makes an effort to solve the problem and achieves the result, we call that a responsible attitude. You’ve probably noticed that in companies, the most responsible people are the executives and key staff, and temporary employees show the greatest irresponsibility. Why are levels of responsibility so different in people, even with a similar education and upbringing?

We also find that, that same person exhibits different level of responsibilities in different areas of his life. A salesperson may work hard on closing the deal but absolutely doesn’t care about writing the report. An accountant may scrupulously work on documents, but can easily ruin the relationship with a fastidious client. The executive can persistently train his employees, then leave them without any supervision to fail.

In one of his articles[20]20

L. Ron Hubbard’s article «The Top Triangle», written on February 18, 1972.

[Закрыть], L. Ron Hubbard described a simple and practical law, which allows an executive to understand the laws responsibility and how to cultivate it in employees. This law takes form of a triangle where the corners are designed as Knowledge, Responsibility, and Control (KRC). We have briefly discussed responsibility, now let's define the remaining corners in sequence. Knowledge is awareness in a particular subject, understanding its nature, and having the necessary data. Control is the ability to regulate the object and change its condition at will. All three components are directly connected and influence each other.

When the Knowledge corner grows larger, a person receives data about an object or an area of activity, which gives him the opportunity to better "control" the object by changing its condition. By "control", generally is the observation of what happens to an object, the collection and evaluation of information about the changes, i.e. "monitoring". But, monitoring is only a part of control, though an important one. To control, i.e. direct the activities of the Sales Department, an executive needs to observe the salespeople under him. Control, as a condition, is where the executive is able to direct the activities of salespeople so that they prepare for negotiations, apply sales techniques properly, close deals successfully and process documents. If he manages to direct their work in such a way, he has control. If he only observes and draws conclusions – then he is only monitoring. A salesperson, in turn, has control over the process of selling to the customer. If he is able to get a meeting with him, steer negotiations in the desired direction, and close the deal. He now has his own area of control.

How sales managers exercise control, depends directly on their level of knowledge. They should know well who they’re managing, and the techniques and tools needed to achieve the desired result. Therefore, the Knowledge corner is where the KRC triangle usually starts expanding.

If a person were to take responsibility for an area and started controlling it, he arrive to some results – positive or negative. If a person knows the tools for the area and has the technology to complete job, he will obtain the expected positive results. A competent executive gives a correct order and his employees follow it. Therefore, his confidence in his ability to influence this area increases. A well-trained salesperson, faced with a customer’s objection, handles this objection and makes the sale. He realizes that he correctly handled objections, and his confidence grows. Then, his responsibility grows. If people were competent in their areas of work and could successfully control it, their responsibility would constantly grow.

We have to deal with an array of diverse tasks, and we are not always competent enough to handle all of them. In the previous chapter, I described the basic functions of an organization. To this day, I’ve yet to meet an executive who is equally competent in each of them. Many executives who work for successful companies, if asked whether they would have taken up a project had they known all the complexities and subtleties involved, answer no. This is not surprising, as the Knowledge corner increases gradually. Real knowledge is not just a collection of information, but includes application. If a person receives too much information without the ability to apply it, he will forget most of it. This information does not become knowledge. Additionally, a person’s knowledge is never absolute. Regardless of what he does, in the process of control he will get positive and negative results.

When a person can’t succeed at a task or handle a situation, he won’t be able to control the activity and gain the desired outcome. He will then generally refuses to take responsibility. Even in something as simple as driving, if a person is not getting results, he will give up the responsibility and say, "Driving is just not for me, I’ll take a taxi".

A successful salesperson who is really good at handling clients is nominated for the sales manager position. Now, he encounters an area that is new to him: controlling his former colleagues. And while he was taught sales, he was never taught how to deal with employees below him – he might fail. He’s leaving his comfort zone, where he had positive results, and now has to act in an area where he doesn’t have any knowledge. This becomes a moment of truth, as he has to make a decision: he can either be causative in this area and deal with this new activity, or he will not be at the cause over this area and will shirk blame to someone else. Letting go responsibility by deciding that “someone else should have taken care of it” is incredibly trite. This "someone" could be anybody, from his parents who gave him a poor upbringing, to his subordinates, or even modern society which does not instill a proper attitude towards work.

The corners of the triangles (KRC) are never fixed. In anybody’s life, there are areas for which they are not taking responsibility. Personally, I can name a tremendous number of areas that I do not take responsibility for, starting with global matters as the environmental deterioration of the planet, and ending with the scratches on the rear bumper of my car (caused by a clueless driver, obviously). On a serious note, responsibility in any area can be increased or decreased via a personal decision. When somebody encounters negative consequences from control and decides to become at the effect, rather than at the cause, and shifts the responsibility, he degrades in that area. On the other hand, if he realizes that this area is under his control and seeks out solutions (such as knowledge, understanding of the subject, etc), he’ll finally get positive results, and his responsibility level will increase.

Even as you read this book, you may think that this is all too difficult and there are too many things to understand. And those things will also need to be applied! But this becomes a question of your goals, and it’s up to you how to answer it. If you decide that you are able to work it out, and then you do so, your confidence in your ability to create a company that runs like clockwork will grow. Therefore, your level of responsibility will grow as well.

It’s interesting to see how people deal with a situation of crisis. Most executives decide, "We are not at the cause. Someone else did this and he should be the one to fix everything." Or they’ll say, "This is a government issue. We just need to wait it out". The competent other executives decide to look into the situation, how consumer preferences are changing, or how the markets are changing. They look for knowledge and solutions. And if they succeed, they’ll use these changes to create success in their business. As a result, their area of responsibility improves, as well as their business.

I have repeatedly observed an experienced executive who can perfectly manage his employees and follows through on complex projects, but cannot handle a crew of workers repairing a fence near his home. The reason for this failure is simple. You need to use different management tools, simpler and more rudimentary. To communicate an idea to a construction worker, you have to use a different language. And though he can do it, he decides that it is not his responsibility, and that the need for money or professional pride will force them to complete the job. As a result, instead of enjoying a good fence, he complains that the world is unfair, and is at the effect of the actions taken by the crew that he had hired himself.

Sometimes a person is denied the possibility to exercise control in his area of responsibility. For example, an employee lacks the tools to achieve compliance from others, even though the results of his work depends on them. Or an executive cannot reward or penalize his subordinates and cannot improve the technology for producing the product in his division, which, in turn, limits his control. His responsibility will then be reduced down to the level of control he is able to exercise. Even his knowledge in this situation will remain a useless theory.

Understanding the KRC triangle provides one with a new outlook on his own difficulties. But here is an interesting point in the work of an organization. If an employee does not have the exact idea of the product expected of him, he is not able to recognize the consequences of his control. Have you ever noticed that the best way to ensure employees were training and improving is to perform strict certifications and verify their skill level and knowledge? Only after he was certified will an employee be able to detect an area where his competence falls short. That will create an agreement with the fact that training is necessary and create a desire to train. It’s in that moment where he begins observing the consequences of his control. He’ll also decide whether he wants to continue his professional activity (and this is an "at cause" decision) and "raise" his Knowledge corner.

In an organization where functions are mixed up and the products expected are ill-defined, responsibility for results cannot be at a high level. Only if each employee understands the line between his functions and those of others, and if there is a quantitative measurement of results, can responsibility grow. The KRC triangle is also called The Triangle of Competence, and the basis for team competence as a whole, is an accurate distribution of functions.

When you provide an accurate org board, distribute its functions wisely among the employees you have, and measure the results quantitatively, this creates the foundation for long-term growth of competence in the entire company.

Chapter 8

Statistics

Understanding the functions that make up an organization allows one to quantitatively measure the results of each one. Many executives want to quantify the work performed by their employees, and they can successfully do that with certain positions, such as salespeople or technicians. In the case of a salesperson, it’s easy because his functions are clear, he has to sell, and then sell some more. Quantifying this result isn’t difficult – it’s either the gross income from his sales or the margin[21]21

Margin: in business, the difference between price and cost (synonym of the term profit). It can be expressed both in absolute values (e.g., USD) and in percentage, as the ratio of price and cost difference to price (unlike retail markup, which is calculated as the same difference to cost).

[Закрыть]. An executive can compare the number of daily (or weekly) sales to the same values from the previous periods, and can easily evaluate whether a salesperson is improving or not. In the previous chapter we looked at the KRC triangle and the process of fostering responsibility. Measuring results quantitatively is an invaluable tool for a manager to impartially evaluate the effects of his control, while discounting excuses and exaggerations. In the case of a salesperson, the evaluation is straightforward – revenue either goes up or down, so things are either going better or worse.

Here you can see something quite phenomenal – people who truly take responsibility for something, as a rule, know and can tell you how much of the product was produced. If the head of the company worked hard on its expansion – he developed plans, searched for solutions to obstacles, achieved compliance – he will easily tell you the quantitative changes in the company. If the advertising department manager planned an advertising campaign to bring a certain number of customers to the stores and worked on achieving that, he knows exactly how many customers a given promotion has brought in. Even outside the office, if a parent works hard on his child’s progress in school, he knows exactly what his child’s grades are, and if he does not know, that means he is not taking responsibility for it.

Responsibility is based on one’s desire to be cause over an area. And that is the reason why one of its components is an ability to observe the consequences of actions. A businessman inspires more confidence if he is fluent with the numbers in his field. If he flounders around, he can look like a windbag. So when we want to convince someone of our competence (which consists of KRC), we demonstrate through our knowledge, the results of our control, and present a lot of numbers, which confirms our ability to observe the consequences of control. Intelligent people intuitively use this law, even if they don't know its exact wording.

We can also say, that for any position or work that has a specific result, you can find a way to measure that result. We perform actions in a material universe and any product that a person creates in this universe is tangible and measurable. This is true even when it comes to such a delicate area as art. If a composer creates an amazing symphony, this is quite a tangible result: you can listen to the music, hear it again, write it down on paper, etc. Therefore, this product can be measured with the number of individual sounds, the degree of the music’s emotional impact, and the number of people who want to hear it again. The work of an interior designer is to create a residential space according to the customer’s preferences and that provides him with harmony, comfort, and convenience. How can we quantify this result? Perhaps, in man hours spent on a project, but that would not entirely make sense. As experience tells us, time can be used differently, with different results. Maybe we should measure the number of blueprints, drawings, or the degree of customer satisfaction? That’s pretty complex. Common sense suggests that in order to evaluate an activity we should have a main criterion. It is impossible to focus on several criteria at once, as one may show improvement in one and deterioration in the other. It’s impossible to make an overall evaluation.

If we take an objective look at the work of an interior designer, we will see that a successful designer works with large areas, while an unsuccessful one does some designs for small spaces from time to time. Therefore, an acceptable measure would be the, “total area with drawn up designs approved by the customer”. Note, that I do not suggest this criterion to compare different designers. We are talking about the designer himself measuring his own results, so that by comparing them regularly he could correctly evaluate whether he is doing better or worse. If this number grows over time, then everything is going well, he gets more and more results, and his sphere of responsibility increases.

When a professional writer creates a manuscript, he counts written words, time spent, and keeps track of his average daily production. This enables one to evaluate the results of his work very accurately and predict any consequences. When the results go down, he has to sort out why this is happening, make conclusions, and change something in the way his work is organized. This is the only way to achieve his goal, as any book is expected to have certain content and volume.

In order to determine the method of measuring results quantitatively, first formulate the VFP for that activity. For example, the supermarket cashier’s VFP is, "payment for goods received swiftly, politely, and with no errors." This is easily quantifiable – you need to count up the amount of money collected in the cash register. In the Hubbard Management System, the word "statistics" is a special term, used to describe a quantitative measurement of the product. Statistical graphs are used to conveniently monitor changes in the amount of product over time.

Thus, a cashier’s statistic is the “amount of monies collected”, and the statistic of an interior designer is the “total area with designs accepted by the customer”. If we take a manager of an auto shop, his job is to ensure the shop’s coordinated operation. Like any executive, he is responsible for the overall product of the area he’s overseeing so his statistic is a “total value of high-quality repairs done". This description does not contain the concept of "payments received for jobs" or “profit”, though both are very important. I’ll talk about who in an organization is responsible for the profit and for receiving money from customers in a later chapter. Note, that in the description of statistic, it also contains the concept of "high-quality". To calculate such statistics quantitatively, we definitely need precise standards of what is considered a high-quality repair and what is not. Usually, by "high-quality", we mean a timely performed repair with which the client is satisfied, and which will not require further repairs in the near future.

Next, how often should one track these quantitative measurements? Should they be done daily, weekly, monthly,quarterly, or yearly? From experience it was found that in most lines of work, one week is the ideal time period for measuring results quantitatively. This is simply because measuring is necessary to promptly identify and eliminate failures in performing functions. In previous chapters, I gave an example of an income flow in a printing company. Imagine that the product quantity was measured only once a month, and something happened in the department responsible for direct marketing. As a result, the amount of promotion sent out to potential customers dropped noticeably right in the beginning of a reporting period. Four weeks will go by before their executive detects the problem, and, unfortunately, will inevitably reduce their sales volume. If mail delivery takes another week, then even if the executive calls for all hands on deck[22]22

All hands on deck: a signal used on board ship, typically in an emergency, to indicate that all crew members are to go on deck. Over time this expression has come to mean that everyone’s help is needed, especially to do a lot of work in a short amount of time.

[Закрыть] and immediately increases the volume of mailed promotion, their Sales Department won’t see its impact as customer influx for another couple of weeks. That means, that the number of new customers to close business with, will decrease for at least two weeks, and the income will drop. A month is too long of a period for managing a growing company. If results are measured just once a month, especially if statistics become available only a few days after the end of the month, it does not allow for corrective actions in a timely manner.

The time period, used by the executive, to evaluate the status of key points in his organization can be compared to how often a ship captain adjusts the ship’s course at sea. If there are not enough "points of adjustment", the course will be similar to a rollercoaster; the path to the port of destination will be too long, consumption of fuel too high, and it will take too much time. For a growing company, to only have 12 moments to “adjust the course" a year, is too little. In addition, a week is much more of a natural period for measuring results than a month. Most companies keep the same weekly schedule for its employees and each week has the same number of business hours. Whereas, months begin and end on different days of the week; months have a different number of both calendar and business days, which makes it more difficult to compare monthly results to each other.

The value of measuring results quantitatively is that any employee can impartially evaluate whether he is doing better or worse, draw appropriate conclusions, and create a step-by-step plan to improve the situation in his area. It is important that it’s easy for them to correlate their results with what was going on at work. If measurements are only done once a month, an employee usually can't even remember the details of what he was doing a month ago. Therefore, in his work, he will not be able to change what actually requires correction and will not be able to repeat what was successful. A week is a different matter. Usually, people can remember quite well what they were doing last week and can correlate their actions with their results. Moreover, most employees find it much easier to create a plan of specific actions for a week’s period, rather than for a month.

For statistics to become a business tool, the employee should have their statistics graph posted at his workplace, which allows him and his supervisor to objectively evaluate his performance. Perhaps, you've visited companies where they had one or more statistics graphs posted at each workstation. In small businesses, where employees combine several functions, it is particularly important that they have separate graphs for each of their main functions.

Making a product can be broken down into components. For example, for the head of the Sales Department, the VFP is “the income received by his department”, and the subproducts are:

• new potential clients procured

• negotiations/presentations done

• contracts signed

• income received

If he controls each of those components, has an idea where the statistics of new customers and negotiations need for desired level of sales, then he can easily plan results by watching the statistics. He will be able to accurately evaluate what he needs when managing the department staff to obtain stable sales growth. To do this, it makes sense for the department executive to have such a set of statistics at his workplace.

An employee maintains his own statistical graph and sees the rise or fall of his performance. That alone has an amazing impact on his efficiency. When we implement this approach in companies, we find that employees gladly show everybody their rising graphs, and are very unhappy when they go down.

There is a category of employees who will fiercely resist having results measured. These are the people who do not want their production level to be obvious to executives. They say it's, "too simplistic", "distracts them from work" or "it takes too long". This person doesn't want his results to become obvious because he, for some reason, is trying to hide them. The most common reason for this is the lack (or very low level) of results. Simply put, this is a slacker who tries to hide his lack of production. Remember, the most productive employees are not only willing to have the results measured, they love it, and usually enthusiastically encourage everybody in the company to have statistics.

Organization is a coordinated flow of production. Therefore, a situation may arise when some part of the company experiences a decline in production, and the reason for this drop is that someone earlier in the flow does not perform their functions. For example, a printing company has problems in the department that produces printing plates. The printing department does not receive completed plates, although they are ready to print and have everything else they needed. Naturally, if the drop in the statistics of the printing plates Department is not resolved in a timely manner, this will bring down statistics in both the printing and shipping Departments. In such cases, the printing Department employees will assert that their statistics are unfair as they are ready to work, ready to produce, and that the drop occurred is not at their fault. Often, they propose to change the wording of their statistics. For this case, they might change it to “percentage of publications produced on-time, for which printing plates were supplied”. At first glance that sounds reasonable, but if we move away from the principle of measuring a product quantitatively and change the way of counting statistics, the new “percentage” statistics will cease to reflect the volume of production. As a result, the statistical system will stop working. It will not be possible to use it to evaluate results, because if they receive the printing plates (production at full capacity) it will show 100 %, and, if they don’t receive the plates, (no production whatsoever) it will still be at 100 %. In this case, statistics will completely lose their main purpose – making it possible to estimate the quantity of VFP produced.

What should an executive do in this a situation? Of course, he needs to recognize that the drop of statistics in the Printing Department wasn’t the fault of its employees, and start urgently fixing the printing plates department. Perhaps, he accidentally kept the printing plates department busy with extra work, and now has to cope with the consequences of his managerial mistake.

You’ve probably noticed that there are companies where all employees work as a coordinated team, take care of each other, and demand results from each other. There are also companies where each employee or department wages a cold war with each other. Usually, the reason for this war lies in the lack of understanding that the company operates a single flow, and how one part of the company affects the performance of other parts. Even in my own production company, at one point, I faced this. My Sales Department was waging war against Production. Only after the organizing board and statistical system were created, implemented, and used for a few months where employees became sufficiently aware of how their actions affected each other, the situation changed, and we got sincere cooperation.

Imagine that in your company, thanks to the org board and statistics, each employee understands exactly the flow of production and where the problems are in this flow that affect the overall result. This creates a completely different atmosphere of cooperation and mutual responsibility.

Therefore, in order to manage an organization effectively, you need to:

1. Have all the necessary products present on the org board in correct sequence.

2. Assign each product to an employee who will be responsible for it and make it possible for others to find out who it is.

3. Determine the method of measuring each product – statistics.

4. Ensure that statistics measure results and not the “willingness to produce".

5. Ensure that employees can calculate their own statistics.

Правообладателям!

Данное произведение размещено по согласованию с ООО "ЛитРес" (20% исходного текста). Если размещение книги нарушает чьи-либо права, то сообщите об этом.Читателям!

Оплатили, но не знаете что делать дальше?