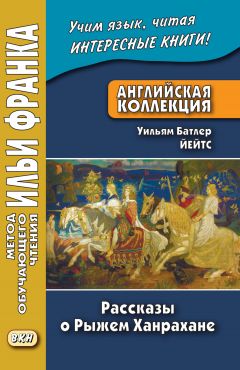

Текст книги "Английская коллекция. Уильям Батлер Йейтс. Рассказы о Рыжем Ханрахане / W. B. Yeats. Stories of Red Hanrahan"

Автор книги: Уильям Йейтс

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +16

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

Red Hanrahan’s curse

(Проклятие Рыжего Ханрахана)

One fine May morning a long time after Hanrahan had left Margaret Rooney’s house (одним ясным майским утром, много дней спустя: «много времени» после того, как Ханрахан покинул Маргарет Руни; fine – превосходный, высшего качества; ясный, хороший /о погоде/), he was walking the road near Collooney (шел он по дороге неподалеку от Кулуни), and the sound of the birds singing in the bushes (и пение птиц, доносившееся из кустов: «звучание птиц, поющих в кустах») that were white with blossom (которые были белы от первоцвета) set him singing as he went (побудило и его запеть в пути: «когда он шел»). It was to his own little place he was going (шел он к своему собственному маленькому жилищу), that was no more than a cabin, but that pleased him well (которое было не более, чем лачугой, но очень радовало его; well – хорошо, отлично; очень, весьма). For he was tired of so many years of wandering from shelter to shelter at all times of the year (поскольку он устал от стольких лет скитаний по чужим порогам круглый год: «от убежища к убежищу во все времена года»),

one [wʌn], bird [bɜ:d], please [pli:z]

One fine May morning a long time after Hanrahan had left Margaret Rooney’s house, he was walking the road near Collooney, and the sound of the birds singing in the bushes that were white with blossom set him singing as he went. It was to his own little place he was going, that was no more than a cabin, but that pleased him well. For he was tired of so many years of wandering from shelter to shelter at all times of the year,

and although he was seldom refused a welcome (и хотя ему редко отказывали в радушном приеме) and a share of what was in the house (и в доле того, что было в этих домах), it seemed to him sometimes that his mind was getting stiff like his joints (ему казалось порой, что ум его коченеет, как его суставы; stiff – жесткий, тугой, негибкий; окостеневший, одеревенелый), and it was not so easy to him as it used to be (и ему уже не так легко, как бывало когда-то) to make fun and sport through the night (шутить и насмехаться /над кем-то/ всю ночь напролет; to make fun – шутить, насмехаться; to make sport – высмеивать; through /зд./ – указывает на совершение действия в течение целого периода времени), and to set all the boys laughing with his pleasant talk (и заставлять всех парней смеяться от его веселой болтовни; pleasant – приятный; веселый, шутливый), and to coax the women with his songs (и улещивать женщин своими песнями). And a while ago, he had turned into a cabin (и вот не так давно он набрел на хижину; to turn – поворачивать; направляться; a while ago – недавно) that some poor man had left to go harvesting and had never come to again (которую какой-то бедняк оставил, чтобы пойти собирать урожай, и так больше и не вернулся назад; harvest – сбор урожая; урожай; to harvest – собирать урожай).

although [ɔ:l'ðǝʋ], laugh [lɑ:f], coax [kǝʋks]

and although he was seldom refused a welcome and a share of what was in the house, it seemed to him sometimes that his mind was getting stiff like his joints, and it was not so easy to him as it used to be to make fun and sport through the night, and to set all the boys laughing with his pleasant talk, and to coax the women with his songs. And a while ago, he had turned into a cabin that some poor man had left to go harvesting and had never come to again.

And when he had mended the thatch (а когда он починил крышу) and made a bed in the corner with a few sacks and bushes (соорудил постель в углу из нескольких мешков и прутьев: «и кустов»), and had swept out the floor (и вымел пол; to sweep), he was well content to have a little place for himself (то был очень рад, что у него есть теперь свой домишко: «что имеет маленький домик для себя»; content – удовлетворенный; довольный), where he could go in and out as he liked (куда он может приходить и /откуда/ уходить, когда пожелает), and put his head in his hands through the length of an evening (и /сидеть/, положа голову на руки, на протяжении всего вечера) if the fret was on him, and loneliness after the old times (если на него накатывало раздражение, одиночество /или тоска/ по былым временам; loneliness – одиночество). One by one the neighbours began to send their children in (один за другим соседи стали посылать своих детей) to get some learning from him (чтобы /те/ получили какие-нибудь знания от него), and with what they brought, a few eggs or an oaten cake or a couple of sods of turf (и из того, что они приносили, – нескольких яиц, овсяной лепешки или пары кусков торфа; sod – дерн), he made out a way of living (он и черпал средства к существованию; to make – составлять, формировать; way – путь, средство; living – образ жизни, жизнь).

content [kǝn'tent], oaten ['ǝʋtn], turf [tɜ:f]

And when he had mended the thatch and made a bed in the corner with a few sacks and bushes, and had swept out the floor, he was well content to have a little place for himself, where he could go in and out as he liked, and put his head in his hands through the length of an evening if the fret was on him, and loneliness after the old times. One by one the neighbours began to send their children in to get some learning from him, and with what they brought, a few eggs or an oaten cake or a couple of sods of turf, he made out a way of living.

And if he went for a wild day and night now and again to the Burrough (и если он время от времени уходил, чтобы сутки напропалую кутить в Бэрроу; wild /зд./ – распущенный, разгульный; day and night – день и ночь, круглые сутки), no one would say a word, knowing him to be a poet, with wandering in his heart (никто не говорил ни слова, понимая, что он поэт и бродяжничество у него в душе: «с бродяжничеством в сердце»).

It was from the Burrough he was coming that May morning, light-hearted enough (как раз из Бэрроу он и шел тем майским утром, совершенно ни о чем не заботясь; light-hearted – беззаботный, беспечный), and singing some new song that had come to him (и напевал одну новую песню, что пришла ему /на ум/). But it was not long till a hare ran across his path (но спустя некоторое время дорогу ему перебежал заяц; long – долгий срок, длительный период), and made away into the fields, through the loose stones of the wall (и ускакал в поля сквозь щель между камнями в стене: «сквозь незакрепленные/расшатанные камни стены»; to make away – удрать, улизнуть; loose – свободный; плохо скрепленный).

would [wʋd], enough [ɪ'nʌf], path [pɑ:θ]

And if he went for a wild day and night now and again to the Burrough, no one would say a word, knowing him to be a poet, with wandering in his heart.

It was from the Burrough he was coming that May morning, light-hearted enough, and singing some new song that had come to him. But it was not long till a hare ran across his path, and made away into the fields, through the loose stones of the wall.

And he knew it was no good sign a hare to have crossed his path (он знал, это нехороший знак, если заяц перебегает ему дорогу), and he remembered the hare that had led him away to Slieve Echtge (и он вспомнил того зайца, который увел его к Слив-Эхтге) the time Mary Lavelle was waiting for him (в тот раз, когда Мэри Лэвелл ждала его), and how he had never known content for any length of time since then (и как он с тех пор не знал покоя ни единой минуты: «любую долготу времени»; content – удовлетворение, довольство; length of time – промежуток: «долгота» времени). “And it is likely enough they are putting some bad thing before me now,” he said (весьма вероятно, что теперь мне подстроят какую-нибудь каверзу: «положат какую-то плохую вещь передо мной», – сказал он).

And after he said that he heard the sound of crying in the field beside him (и после того как сказал это, он услышал плач в поле рядом с ним), and he looked over the wall (и заглянул за стену). And there he saw a young girl sitting under a bush of white hawthorn (он увидел молодую девушку, сидящую под кустом белого боярышника), and crying as if her heart would break (и плачущую так, будто ее сердце /вот-вот/ разорвется).

sign [saɪn], likely ['laɪklɪ], break [breɪk]

And he knew it was no good sign a hare to have crossed his path, and he remembered the hare that had led him away to Slieve Echtge the time Mary Lavelle was waiting for him, and how he had never known content for any length of time since then. “And it is likely enough they are putting some bad thing before me now,” he said.

And after he said that he heard the sound of crying in the field beside him, and he looked over the wall. And there he saw a young girl sitting under a bush of white hawthorn, and crying as if her heart would break.

Her face was hidden in her hands (ее лицо было спрятано в ладонях; to hide), but her soft hair and her white neck and the young look of her (но ее мягкие волосы, ее белая шея и ее юный вид), put him in mind of Bridget Purcell and Margaret Gillane and Maeve Connelan and Oona Curry and Celia Driscoll (напомнили ему Бриджет Перселл, и Маргарет Гилэйн, и Мэйв Коннелан, и Уну Керри, и Селью Дрисколл; to put smb. in mind of – напоминать кому-л. о /ком-л., чем-л./), and the rest of the girls he had made songs for (и остальных девушек, для которых он слагал песни) and had coaxed the heart from with his flattering tongue (и чьи сердца обвораживал своим льстивым языком; to coax – уговаривать, задабривать).

She looked up, and he saw her to be a girl of the neighbours, a farmer’s daughter (она подняла глаза: «посмотрела вверх», и он увидел, что это соседская девушка, фермерская дочь). “What is on you, Nora?” he said (что с тобой, Нора? – спросил он). “Nothing you could take from me, Red Hanrahan (ничего, что ты мог бы забрать от меня = от чего бы ты мог избавить меня, Рыжий Ханрахан).”

hidden ['hɪdn], flattering ['flæt(ǝ)rɪŋ], tongue [tʌŋ]

Her face was hidden in her hands, but her soft hair and her white neck and the young look of her, put him in mind of Bridget Purcell and Margaret Gillane and Maeve Connelan and Oona Curry and Celia Driscoll, and the rest of the girls he had made songs for and had coaxed the heart from with his flattering tongue.

She looked up, and he saw her to be a girl of the neighbours, a farmer’s daughter. “What is on you, Nora?” he said. “Nothing you could take from me, Red Hanrahan.”

“If there is any sorrow on you (если у тебя есть какая-то печаль) it is I myself should be well able to serve you,” he said then (я самолично вполне смог бы послужить тебе, – сказал он тогда), “for it is I know the history of the Greeks (ибо мне ведома история греков), and I know well what sorrow is (и мне хорошо известно, что такое печаль) and parting, and the hardship of the world (и расставание, и невзгоды этого мира; hardship – трудность, трудности, неприятность, неприятности). And if I am not able to save you from trouble,” he said (а ежели я окажусь не в силах спасти тебя от горя, – сказал он), “there is many a one I have saved from it with the power that is in my songs (то многих я спас от него силой, которая заключена в моих песнях; many a one – многие), as it was in the songs of the poets (которая заключалась в песнях поэтов) that were before me from the beginning of the world (которые были = жили до меня от начала этого мира). And it is with the rest of the poets I myself will be sitting and talking in some far place (и с остальными поэтами я и сам буду восседать и беседовать в некоем отдаленном месте) beyond the world, to the end of life and time,” he said (за пределами этого мира, до скончания жизни и времени, – сказал он).

serve [sɜ:v], power ['paʋǝ], beyond [bɪ'jɒnd]

“If there is any sorrow on you it is I myself should be well able to serve you,” he said then, “for it is I know the history of the Greeks, and I know well what sorrow is and parting, and the hardship of the world. And if I am not able to save you from trouble,” he said, “there is many a one I have saved from it with the power that is in my songs, as it was in the songs of the poets that were before me from the beginning of the world. And it is with the rest of the poets I myself will be sitting and talking in some far place beyond the world, to the end of life and time,” he said.

The girl stopped her crying, and she said (девушка прекратила рыдать и сказала), “Owen Hanrahan, I often heard you have had sorrow and persecution (Оуэн Ханрахан, я часто слышала, что ты испытал на себе горе и гонения), and that you know all the troubles of the world (и что тебе знакомы все невзгоды мира) since the time you refused your love to the queen-woman in Slieve Echtge (с того времени, как отказал в своей любви женщине-королеве в Слив-Эхтге); and that she never left you in quiet since (и что с тех пор она совсем не оставляет тебя в покое; never /зд./ – нисколько, никоим образом /эмоц. – усил./). But when it is people of this earth that have harmed you (но когда земные люди причинили тебе зло), it is yourself knows well the way to put harm on them again (ты сам прекрасно знаешь способ, как вернуть им его назад: «наложить зло на них снова»; harm – вред, ущерб; зло). And will you do now what I ask you, Owen Hanrahan?” she said (но сделаешь ли ты сейчас то, о чем я тебя попрошу, Оуэн Ханрахан? – спросила она). “I will do that indeed,” said he (конечно же, я это сделаю, – сказал он; indeed – действительно, в самом деле; конечно, безусловно /усил./).

often ['ɑ:fn], persecution [,pɜ:sɪ'kju:ʃ(ǝ)n], harm [hɑ:m]

The girl stopped her crying, and she said, “Owen Hanrahan, I often heard you have had sorrow and persecution, and that you know all the troubles of the world since the time you refused your love to the queen-woman in Slieve Echtge; and that she never left you in quiet since. But when it is people of this earth that have harmed you, it is yourself knows well the way to put harm on them again. And will you do now what I ask you, Owen Hanrahan?” she said. “I will do that indeed,” said he.

“It is my father and my mother and my brothers,” she said (мой отец, моя мать, и мои братья, – сказала она), “that are marrying me to old Paddy Doe (выдают меня за старого Пэдди Доу), because he has a farm of a hundred acres under the mountain (потому что у него есть ферма в сотню акров под горой). And it is what you can do, Hanrahan,” she said (и вот, что ты можешь сделать, Ханрахан, – сказала она), “put him into a rhyme the same way you put old Peter Kilmartin in one (вставь его имя в стих, как ты вставил в него /имя/ Питера Килмартина; the same way – таким же образом) the time you were young (в то время, когда ты был молод), that sorrow may be over him rising up and lying down (пусть эта печаль будет /нависать/ над ним, /когда он/ встает и /когда/ ложится; to rise up – вставать /с постели/), that will put him thinking of Collooney churchyard and not of marriage (что заставит его думать о погосте в Кулуни, а не о женитьбе; to put /зд./ – заставлять /кого-л. делать что-л./; churchyard – церковный двор /арх./; кладбище /при церкви/).

rhyme [raɪm], churchyard ['tʃɜ:tʃ,jɑ:d], marriage ['mærɪdʒ]

“It is my father and my mother and my brothers,” she said, “that are marrying me to old Paddy Doe, because he has a farm of a hundred acres under the mountain. And it is what you can do, Hanrahan,” she said, “put him into a rhyme the same way you put old Peter Kilmartin in one the time you were young, that sorrow may be over him rising up and lying down, that will put him thinking of Collooney churchyard and not of marriage.

And let you make no delay about it (да не мешкай с этим: «насчет этого»; to make no delay – не задерживаться), for it is for tomorrow they have the marriage settled (потому что уже на завтра они назначили свадьбу; to settle – поселяться, обосновываться; договариваться, определять), and I would sooner see the sun rise on the day of my death than on that day (а я скорее увижу восход солнца в день своей смерти, чем в этот день).”

“I will put him into a song that will bring shame and sorrow over him (я вставлю его /имя/ в песню, которая принесет ему стыд и горести); but tell me how many years has he (но скажи мне, сколько лет ему), for I would put them in the song (чтобы я упомянул о них в песне)?”

“O, he has years upon years (о, ему уже лет и лет). He is as old as you yourself, Red Hanrahan (он так же стар, как и ты сам, Рыжий Ханрахан).” “As old as myself,” said Hanrahan, and his voice was as if broken; “as old as myself (так же стар, как я, – сказал Ханрахан, и его голос как будто треснул, – так же стар, как я); there are twenty years and more between us (меж нами более двадцати лет /разницы/)!

tomorrow [tǝ'mɒrəʋ], sooner ['su:nǝ], myself [maɪ'self]

And let you make no delay about it, for it is for tomorrow they have the marriage settled, and I would sooner see the sun rise on the day of my death than on that day.”

“I will put him into a song that will bring shame and sorrow over him; but tell me how many years has he, for I would put them in the song?”

“O, he has years upon years. He is as old as you yourself, Red Hanrahan.” “As old as myself,” said Hanrahan, and his voice was as if broken; “as old as myself; there are twenty years and more between us!

It is a bad day indeed for Owen Hanrahan (это поистине дурной день для Оуэна Ханрахана) when a young girl with the blossom of May in her cheeks (если юная девушка с майским цветением на щечках) thinks him to be an old man (считает его стариком). And my grief!” he said, “you have put a thorn in my heart (о горе мне! – сказал он, – ты вонзила шип в мое сердце).”

He turned from her then and went down the road till he came to a stone (он отвернулся от нее и побрел по дороге, пока не подошел к камню), and he sat down on it (и он уселся на него), for it seemed as if all the weight of the years had come on him in the minute (ибо, казалось, все бремя этих лет вмиг свалилось на него). And he remembered it was not many days ago (и он припомнил, как не так много дней назад) that a woman in some house had said (женщина в одном доме сказала): “It is not Red Hanrahan you are now but yellow Hanrahan (не Рыжий Ханрахан ты теперь, а желтый Ханрахан), for your hair is turned to the colour of a wisp of tow (потому что твои волосы сделались цвета пучка пакли; to turn – поворачивать; изменяться, менять /цвет, окраску/).”

Owen ['ǝʋɪn], minute ['mɪnɪt], tow [tǝʋ]

It is a bad day indeed for Owen Hanrahan when a young girl with the blossom of May in her cheeks thinks him to be an old man. And my grief!” he said, “you have put a thorn in my heart.”

He turned from her then and went down the road till he came to a stone, and he sat down on it, for it seemed as if all the weight of the years had come on him in the minute. And he remembered it was not many days ago that a woman in some house had said: “It is not Red Hanrahan you are now but yellow Hanrahan, for your hair is turned to the colour of a wisp of tow.”

And another woman he had asked for a drink (а другая женщина, у которой он попросил попить) had not given him new milk but sour (дала ему не парного молока, а прокисшего; new – новый; свежий); and sometimes the girls would be whispering and laughing with young ignorant men (и порой девушки шептались и смеялись с юными невежами) while he himself was in the middle of giving out his poems or his talk (пока он сам во всю читал свои стихи или рассуждал; in the middle of – в середине /чего-л./, во время /какого-л. дела, занятия/; to give out – «выдавать», провозглашать, обнародовать). And he thought of the stiffness of his joints (и он подумал о своих непослушных суставах: «об оцепенении суставов») when he first rose of a morning (когда он встает поутру /с постели/; first – впервые, сперва), and the pain of his knees after making a journey (и о боли в коленях после того, как совершит путешествие), and it seemed to him as if he was come to be a very old man (и ему показалось, будто он уже стал очень старым человеком), with cold in the shoulders and speckled shins and his wind breaking (с ревматизмом в плечах, с ногами в старческих пятнах и с одышкой: «с пятнистыми голенями и прерывистым дыханием»; cold – холод; простуда; wind – ветер; дыхание) and he himself withering away (и сам весь сморщился и высох; to wither – вянуть, сохнуть).

sour ['saʋǝ], whisper ['wɪspǝ], speckled ['spekld]

And another woman he had asked for a drink had not given him new milk but sour; and sometimes the girls would be whispering and laughing with young ignorant men while he himself was in the middle of giving out his poems or his talk. And he thought of the stiffness of his joints when he first rose of a morning, and the pain of his knees after making a journey, and it seemed to him as if he was come to be a very old man, with cold in the shoulders and speckled shins and his wind breaking and he himself withering away.

And with those thoughts there came on him a great anger (и с этими мыслями нашло на него великое озлобление) against old age and all it brought with it (против старости и всего, что она приносит с собой; old age – старческий возраст). And just then he looked up and saw a great spotted eagle (и тут он глянул вверх и увидел огромного пятнистого орла) sailing slowly towards Ballygawley (медленно плывущего в сторону Бэллиголи), and he cried out: “You, too, eagle of Ballygawley, are old (и он крикнул: «Ты тоже, орел из Бэллиголи, стар»), and your wings are full of gaps (и в твоих крыльях полно дыр; gap – брешь, пролом), and I will put you and your ancient comrades (и я помещу тебя и твоих древних товарищей), the Pike of Dargan Lake and the Yew of the Steep Place of the Strangers (Щуку из озера Дарган и Тис с Кручи Чужестранцев; steep – крутой; place – место) into my rhyme (в свой стих), that there may be a curse on you for ever (который, возможно, станет для вас проклятьем навсегда).”

eagle ['i:ɡl], ancient ['eɪnʃ(ǝ)nt], stranger ['streɪndʒǝ]

And with those thoughts there came on him a great anger against old age and all it brought with it. And just then he looked up and saw a great spotted eagle sailing slowly towards Ballygawley, and he cried out: “You, too, eagle of Ballygawley, are old, and your wings are full of gaps, and I will put you and your ancient comrades, the Pike of Dargan Lake and the Yew of the Steep Place of the Strangers into my rhyme, that there may be a curse on you for ever.”

There was a bush beside him to the left, flowering like the rest (неподалеку от него с левой стороны находился куст, цветущий, как и все остальные), and a little gust of wind blew the white blossoms over his coat (и легкий порыв ветра сдул белые лепестки на его куртку; to blow; blossom – цветение; цветок). “May blossoms,” he said, gathering them up in the hollow of his hand (майские цветы, – сказал он, собирая их в ладонь; hollow – пустота, полость; углубление), “you never know age because you die away in your beauty (вам вообще не ведомо старение, потому что вы умираете во /всей/ своей красе), and I will put you into my rhyme and give you my blessing (я помещу и вас в свой стих и дам вам свое благословение).”

He rose up then and plucked a little branch from the bush (тут он поднялся, сорвал небольшую веточку с куста), and carried it in his hand (и понес ее в руке). But it is old and broken he looked going home that day (однако старым и разбитым он выглядел, идя домой в тот день) with the stoop in his shoulders and the darkness in his face (с поникшими плечами и помрачневшим лицом: «с сутулостью в плечах и мрачностью в лице»).

gust [ɡʌst], blew [blu:], darkness ['dɑ:knɪs]

There was a bush beside him to the left, flowering like the rest, and a little gust of wind blew the white blossoms over his coat. “May blossoms,” he said, gathering them up in the hollow of his hand, “you never know age because you die away in your beauty, and I will put you into my rhyme and give you my blessing.”

He rose up then and plucked a little branch from the bush, and carried it in his hand. But it is old and broken he looked going home that day with the stoop in his shoulders and the darkness in his face.

When he got to his cabin there was no one there (когда он добрался до своей лачуги, там не было никого), and he went and lay down on the bed for a while (он пошел и улегся ненадолго на кровать) as he was used to do when he wanted to make a poem or a praise or a curse (что он обычно делал, когда хотел сложить стих, или восхваление, или проклятие). And it was not long he was in making it this time (не долго он сочинял его в этот раз), for the power of the curse-making bards was upon him (поскольку у него: «на нем» была сила бардов, сочиняющих проклятия). And when he had made it (и когда он его сложил) he searched his mind how he could send it out over the whole countryside (он /стал/ раздумывать, как же он сможет разослать его по всей округе: «по всей сельской местности»; to search one’s mind – ломать голову; to search – искать, разыскивать; изучать, исследовать; mind – память; рассудок, ум).

Some of the scholars began coming in then (тут начали приходить школьники), to see if there would be any school that day (чтобы узнать, будут ли занятия в этот день;to see – видеть; узнавать, выяснять; school – школа, учебное заведение; занятия, уроки /в школе/), and Hanrahan rose up and sat on the bench by the hearth (Ханрахан поднялся и сел на скамью у очага), and they all stood around him (а они все встали вокруг него).

search [sɜ:tʃ], whole [hǝʋl], countryside ['kʌntrɪ,saɪd]

When he got to his cabin there was no one there, and he went and lay down on the bed for a while as he was used to do when he wanted to make a poem or a praise or a curse. And it was not long he was in making it this time, for the power of the curse-making bards was upon him. And when he had made it he searched his mind how he could send it out over the whole countryside.

Some of the scholars began coming in then, to see if there would be any school that day, and Hanrahan rose up and sat on the bench by the hearth, and they all stood around him.

They thought he would bring out the Virgil or the Mass book or the primer (они полагали, что он достанет Вергилия, или требник, или букварь), but instead of that he held up the little branch of hawthorn he had in his hand yet (но вместо этого он показал маленькую веточку боярышника, которая все еще была у него в руке; to hold up – показывать, выставлять напоказ). “Children,” he said, “this is a new lesson I have for you today (дети, – сказал он, – вот новый урок, который я приготовил для вас сегодня).

“You yourselves and the beautiful people of the world are like this blossom (вы сами и красивые люди этого мира похожи на это цветение/этот цвет), and old age is the wind that comes and blows the blossom away (а старость – это ветер, который приходит и сдувает это цветение). And I have made a curse upon old age and upon the old men (я сочинил проклятие старости и старикам), and listen now while I give it out to you (теперь слушайте, пока я буду зачитывать: «давать» его вам).” And this is what he said (и вот, что он произнес) —

instead [ɪn'sted], hawthorn ['hɔ:θɔ:n], listen ['lɪsn]

They thought he would bring out the Virgil or the Mass book or the primer, but instead of that he held up the little branch of hawthorn he had in his hand yet. “Children,” he said, “this is a new lesson I have for you today.

“You yourselves and the beautiful people of the world are like this blossom, and old age is the wind that comes and blows the blossom away. And I have made a curse upon old age and upon the old men, and listen now while I give it out to you.” And this is what he said —

The poet, Owen Hanrahan, under a bush of May (поэт Оуэн Ханрахан под майским кустом)

Calls down a curse on his own head because it withers grey (призывает проклятие на свою собственную голову, потому что она поседела; to call down – призывать /проклятия и т. п. на чью-л. голову/; to wither /зд./ – блекнуть; grey – серый; седой);

Then on the speckled eagle cock of Ballygawley Hill (потом – на пятнистого орла, /живущего/ на холме Бэллиголи; cock – петух; самец /любой птицы/),

Because it is the oldest thing that knows of cark and ill (потому что он – старейшее существо, которому ведомы тревоги и невзгоды;thing – существо, создание; ill – зло, вред; несчастья, беды);

And on the yew that has been green from the times out of mind (и на тисовое дерево, что зеленеет с незапамятных времен)

By the Steep Place of the Strangers and the Gap of the Wind (у Кручи Чужестранцев и у Ущелья Ветра; gap – пролом, щель; горный проход, ущелье);

And on the great grey pike that broods in Castle Dargan Lake (и на огромную серую щуку, которая предается раздумьям в Озере близ Замка Дарган; to brood – сидеть на яйцах; размышлять /особ. с грустью/)

Having in his long body a many a hook and ache (имея в своем длинном теле много крючков и ран; ache – боль);

yew [ju:], castle ['kɑ:sl], ache [eɪk]

The poet, Owen Hanrahan, under a bush of May

Calls down a curse on his own head because it withers grey;

Then on the speckled eagle cock of Ballygawley Hill,

Because it is the oldest thing that knows of cark and ill;

And on the yew that has been green from the times out of mind

By the Steep Place of the Strangers and the Gap of the Wind;

And on the great grey pike that broods in Castle Dargan Lake

Having in his long body a many a hook and ache;

Then curses he old Paddy Bruen of the Well of Bride (еще проклинает он Пэдди Бруэна, /живущего/ у Родника Невест)

Because no hair is on his head and drowsiness inside (потому что ни одной волосинки нет на его голове, а душа его уже дремлет: «и дремота внутри»).

Then Paddy’s neighbour, Peter Hart, and Michael Gill, his friend (еще соседа Пэдди, Питера Харта, и Майкла Гилла, его друга),

Because their wandering histories are never at an end (потому что их путаные россказни никогда не /приходят/ к концу; wandering – бродячий; блуждающий, бессвязный).

And then old Shemus Cullinan, shepherd of the Green Lands (и еще старого Шемуса Каллинана, пастуха с Грин-Лэндз)

Because he holds two crutches between his crooked hands (потому что он держит два костыля в своих скрюченных руках);