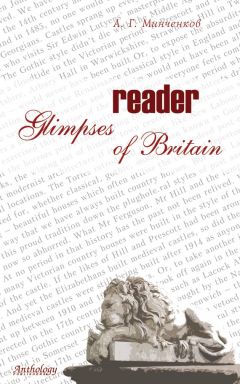

Текст книги "Glimpses of Britain. Reader"

Автор книги: Алексей Минченков

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +12

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 10 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 2 страниц]

Painted Lady of Kew uncovered

The Times

Monday, December 12, 2005

By Dalya Alberge

Experts have uncovered a painted female figure that is part of the original 17th-century decoration of Kew Palace, the summer residence of King George III and Queen Charlotte.

It has emerged from beneath nearly 20 layers of paint in the King’s Library of the palace, which stands in the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

The discovery comes before the palace’s reopening to the public at the end of April.

The work is a grisaille, a style of painting on walls or ceilings in greyish tints that imitate bas-reliefs. Although only a fraction of the decorative scheme has been uncovered so far, the figure – about 16in high – appears to represent a carving for a stone and marble fireplace overmantel.

There is likely to be a corresponding male figure on the other side of the fireplace, but that section has yet to be explored. The 1630s brick building is the last survivor of several important royal residences. Kew was used by the Royal Family between 1729 and 1818. The figure is part of a scheme that is thought to date from the second half of the 17th century.

John Burbidge, a consultant for Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) and a wall paintings conservator, said: “This is one of the earliest bits of decoration to be found in the house. HRP is presenting decoration from the early 19th century, but this predates it, right back to the origins of the house.”

He described the figure as so finely executed that its artist may have been Antonio Verrio, who painted the King’s staircase in Hampton Court Palace, he added.

The discovery was made by Catherine Hassall, a paint analyst. In a painstaking operation, she used a binocular microscope and surgical scalpels to remove the overpaint.

The process is so slow that it takes about an hour for every square centimetre.

Mr Burbidge said that while the results were tantalising, it was not known whether further work would continue: “You’re causing microscopic damage to the surface. Although the image looks intact, there is a conservation issue.”

Kew Palace is one of five unoccupied palaces in the care of HRP, a charitable trust.

The palace has undergone an ambitious restoration costing Ј6.6 million, but HRP is still seeking Ј700,000 to complete the project.

Plans include a new visitor welcome centre and the conservation of objects for display such as the wax head of George III made from a life mask by Madame Tussaud.

The palace was the family country home of George III and his queen between 1800 and 1818. In 1788 the monarch began to show symptoms of mental derangement.

He convalesced at Kew under the watchful eyes of his many doctors, during his well-documented bouts of illness, presumed as madness but now known to have been porphyria. Large parts of the building have remained untouched since Queen Charlotte’s death in 1818, which brought to an end 90 years of royal residence at Kew Palace. Her possessions were removed or sold and a housekeeper was left in residence in the empty house, which was opened to the public in 1899 by Queen Victoria.

Al-Qaeda threat to Queen tightens Cenotaph security

The Times

Monday, November 14, 2005

A warning by al-Qaeda that it views the Queen as an enemy of Islam led to unprecedented security for yesterday’s Remembrance Service at the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

The Queen was identified as “one of the severest enemies of Islam” in an al-Qaeda video issued after the July 7 London suicide bombings. The full text, including the reference to the Queen, was not revealed at the time.

Security sources confirmed that MI5 had carried out an assessment of the implied threat to the Queen, which had been passed to the Metropolitan Police Royalty Protection Branch (SO14).

The sources said that any additional protection measures for the Queen and the Royal Family were a matter for the police. Tighter security for the Queen is also expected later this month at the Commonwealth heads of government conference in Malta.

The video, which highlighted the Queen as an enemy of Islam for the first time, was broadcast in a statement by Ayman al-Zawahiri, who is Osama bin Laden’s deputy. He accused the Queen of being ultimately responsible for Britain’s “crusader laws” against Muslims.

With the memory of July’s London bombings still fresh in everyone’s minds, no one complained about the strict airport-style security at the Remembrance Sunday service at the Cenotaph.

Good-humoured queues of veterans and spectators filed slowly through a bank of security gates at the top of Whitehall. Their bags were checked and their bodies screened by metal detectors as hundreds of police marshalled the crowds.

On the stroke of 11am from Big Ben, those gathered fell silent to remember “The Glorious Dead”, as they are commemorated in the inscription on the white Portland stone. At that moment, the sun broke through the clouds, shining brightly on the assembled civic and military leaders.

The Queen, dressed in black, was first to lay a wreath, followed by the Duke of Edinburgh, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, and the Princess Royal, all in military uniform. Tony Blair, Michael Howard, Charles Kennedy and other political leaders also placed wreaths at the foot of the monument.

Watching from a Foreign Office balcony were Prince William, an army recruit, and the Duchess of Cornwall, appearing at the commemoration for the first time. The duchess revealed a thrifty side by wearing the same hat for the second time in under a fortnight. The black and white creation by Philip Treacy appeared nine days earlier during her tour of the United States as she visited the Second World War memorial in Washington.

After the service about 8,000 veterans paraded past the Cenotaph, their medals glinting in the autumn sunshine. From Gurkhas to the scarlet-coated Chelsea Pensioners, the former servicemen were a moving sight as they marched in time to music such as It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.

At one point a walking stick was dropped, but the owner kept striding on and it was quickly retrieved by others further down the line. Every now and then a young boy would be among a detachment holding his grandfather’s hand or perhaps walking in his place.

Joe Newman, 89, served with the Parachute Regiment and was present at Dunkirk and the D-Day landings. He also served in North Africa and Italy. “I like to remember my friends who fell,” he said, “I lost a lot of friends, especially at Dunkirk.”

The crowds who thronged the pavements reserved their loudest applause for the oldest veterans, many of whom were in wheelchairs or motorised buggies.

In a specially organised tribute, a silent message of remembrance was passed down the River Thames using semaphore. Veterans and signalmen, the first posted on the roof of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, used flags to make the secret code, which was decrypted at Whitehall and attached to a wreath which was laid at the Cenotaph.

The 16 signalling posts included the Cutty Sark, HMS Belfast and HMS St Vincent. The message read: “War turns us to stone. In remembrance we shine and rise to new days.”

In other services around the country, the Earl of Wessex laid a wreath in Sunderland, and in Liverpool a D-Day bomber dropped 100,000 poppies at the St George’s Hall Cenotaph.

If we don’t change now, we’ll all be poorer for it

The Times

Thursday, December 1, 2005

By Christine Seib

The Pensions Commission’s 459-page report and its 309-page appendices give warning that if we do not change our pensions system pensioners will become increasingly poor compared with the rest of society. The only other options – work longer, save more or pay higher tax – are equally unattractive.

We must decide how to balance these choices. The debate has to start now.

The Problem

Pensioners in Britain today are, on average, the richest the country has had because they benefit from generous final-salary pensions and good state second-pension (S2P) rebates. But many pensioner groups are living in poverty, such as women and carers who were unable to work long enough to get a full state pension. Many factors, including meagre state pensions, unpredictable mortality improvements and stock market falls, are gradually increasing the number of people with inadequate retirement provision. The commission believes that the problem cannot be fixed by simple changes to the state pension system or small measures to encourage voluntary saving. Nor can rocketing house prices be considered a replacement for saving for most people.

Solutions

The commission divides its solutions into two “core” parts, with some important additional considerations. The core parts comprise a private sector initiative – a salary-related savings system that is not compulsory but gives workers a push toward saving – and state pension reforms to make state benefits easier to understand and less means-tested.

Private Sector

Lord Turner of Ecchinswell proposes a national pensions saving scheme (NPSS) that could be set up by 2010 or soon after. All workers who do not already have good pension provision would be automatically enrolled but with a right to opt out. They will pay in 4 per cent of their gross pay above Ј5,000 and below Ј33,000. The Government would contribute 1 per cent in tax relief and the employer 3 per cent.

The money would be deducted either through the existing Pay As You Earn system or a new pension payment system and put into the NPSS. Both employee and employer could make higher voluntary contributions.

The NPSS will bulk-buy fund management to keep the cost of managing the nation’s savings at about 0.3 per cent. Savers who want to keep their charges at that level could choose from one of up to ten investment options.

People who want more exotic investments could choose to pay a higher charge. Those who did not want to make any investment choice at all would be put into a default investment fund.

Pros And Cons

Savings rates are declining as more employees are moved from final-salary to defined-contribution occupational pensions. The commission hopes that the NPSS will arrest this decline. But employers, particularly small businesses, complain that they cannot afford to make contributions to their workers’ retirement savings. Lord Turner calls these payments “contingent compulsion” and admits that wages may not grow as quickly because of them. He hopes that the 3 per cent employers’ contribution is not high enough to prompt most bosses to entice their workers out of the NPSS in return for a one-off bonus or other inducement.

Public Sector

The commission proposes a few changes to the state pension: increase the retirement age, increase the basic state pension and reduce means-testing. Lord Turner proposes that we move to a two-part state pension, comprising a basic state pension (BSP) and the S2P. The S2P is an earnings-related additional state pension that people can accrue over their working life. This allows people who do not want to leave their savings with the Government to “contract out” of the S2P and receive a cash rebate that they can pay into a company or personal pension fund.

To create his two-part state pension, Lord Turner recommends that we freeze the upper earnings, Ј32,760, from which workers can accrue S2P. This would gradually reduce the amount of S2P that higher earners can put aside.

Meanwhile, the lower amount at which people are entitled to accrue S2P, Ј12,100, would continue to rise so that over many years, the gap between the differing amounts of S2P accrued by high and low-paid workers would become a flat rate. The commission also wants contracting out of the S2P to be phased out by 2030 so that more money stays in the state system.

By 2010 the commission wants the BSP’s growth to be linked to earnings rather than prices, making it more generous over time. Lord Turner also recommends that the Ј109 upper limit of the means-tested state pension increases only in line with prices, rather than with earnings, as it does currently. As the Ј80 BSP rises with earnings, the gap between the two will gradually close, drastically reducing the number of pensioners receiving means-tested benefits.

To balance a more generous state pension, Britons would have to work longer. Lord Turner recommends that the age at which people could draw a state pension should rise to 66 by 2030 and to 67 by 2050. If mortality rates improve even more quickly than forecast, these figures would have to be adjusted to 69 by 2050.

To address the problem of female pensioner poverty, the commission suggests a flat pension based on residency rather than years in work for the over-75s. But it did not say when this should be introduced, and gave warning that it would push up the commission’s projected costs.

Means-testing

The financial services industry argues that cutting means-testing, which penalises people for saving, will encourage people to put aside more for retirement. But the National Pensioners Convention works out that today’s pensioners will benefit by only Ј1.36 a week more from a BSP-earnings link than they would have under the Government’s current proposals for pension increases.

The commission calculates that its proposed changes to the state pension would cost about Ј1.5 billion a year by 2020 and over the longer-term would take the Government’s expenditure on pensions to as much as 8 per cent of GDP, up from 6.2 per cent currently.

Warriors, statesmen, prelates. Can young David live up to his ancestors?

The Times

Monday October 24, 2005

by William Rees-Mogg

It all turns on Ferdinand Mount, the political columnist who once ran Baroness Thatcher’s policy unit and became a distinguished editor of The Times Literary Supplement. He is the 3rd baronet in the Mount line but does not use the title.

If one wants to discover David Cameron’s genealogy, one has to look up the entry under Mount in Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage: at the foot of the entry appears David Cameron’s name. His mother was the daughter of the 2nd Baronet Mount, who had no male heirs, so she is Ferdy’s first cousin. David Cameron is, therefore, Ferdy’s first cousin once removed. The Mount family, the forebears both of Ferdy and David, married an heiress of the Talbot family in the mid-19th century, before they received their baronetcy. There is a cross-reference to the Talbot entry, which comes under the Earl of Shrewsbury and Waterford.

The 22nd Earl of Shrewsbury is now the Premier Earl of England and Ireland; his original title was created in 1442 for John Talbot, the heroic general who lost his life at Castillon in the final battle of the Hundred Years War. Two of his sons were killed with him, one legitimate, the other a bastard. The French honoured his courage, calling him “the English Achilles”.

John Talbot was a great national hero of the 15th century, second only to Henry V. He was nearly 80 when he fell in battle. They brought his heart home and buried it at Whitchurch in Shropshire under a great Gothic canopy.

In terms of English history, the Talbots are one of the great families, like the Cecils or the Churchills, only much older. Perhaps the Howards are the closest parallel. The Talbots are an 11th-century family. The Cecils are 16th century and the Churchills, like the Foxes, are 17th century.

In the old Dictionary of National Biography there are 20 entries for members of the Talbot family. The most eccentric is Mary Anne Talbot, the “British Amazon”, who joined the Royal Navy as a transvestite, was wounded, fought as a powder monkey in the battle of “The Glorious First of June”, 1794, and subsequently appeared on the stage in Babes in the Wood. She claimed to be an illegitimate daughter of the 1st Earl of Talbot, yet another family earldom.

The more respectable Talbots, apart from their national hero, produced countless earls, two dukes, though one was only a Jacobite duke, a First Minister, one of Sir Robert Walpole’s Lord Chancellors, a Bishop of Durham, a Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, another medieval Archbishop of Dublin, the great building heiress Bess of Hardwick, and William Fox-Talbot, who invented photography. They married many interesting people, including William Herbert, who was Shakespeare’s patron. Through the Talbots of Malahide, they are connected to James Boswell.

David Cameron aims to become Prime Minister; no one was called Prime Minister before Robert Wal-pole, but Cameron does have a family forebear who was First Minister. Charles Talbot, the 12th earl and the first and only Duke of Shrewsbury, was born in 1660. He was the first child after the Restoration to be christened with Charles II as his godfather.

When he was only seven a scandalous tragedy happened in the family. His mother was having an affair with George Villiers, the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, a thoroughly contemptible man, even by the standards of the Restoration Court. His father, the 11th Earl, challenged Buckingham to a duel. Buckingham wounded him fatally. The countess is said to have watched the duel, disguised as a page in Buckingham’s retinue. Immediately after the duel contemporary rumours state that she and Buckingham made love; he was still wearing the shirt stained with her husband’s blood. Not an ideal start in life for her son. Shrewsbury had the knack of holding power at crucial moments in a revolutionary situation. He was the only Secretary of State, and therefore was First Minister, in the first administration appointed by William III in 1689, immediately after the Glorious Revolution. He had been a leading figure in inviting William to invade England, went to Holland to join him, helped to finance the invasion with a loan of Ј12,000, and even went to console James II and persuade him to abdicate. Shrewsbury was First Minister again in the later 1690s, when William spent a long time outside England. Early in the reign of Queen Anne he became disgusted with politics and spent some years on the Continent, but he came back and was appointed First Minister by Queen Anne on her death bed. He was therefore First Minister immediately after the accession of William III, again when Queen Anne died and on the arrival of King George I.

How did he do it? Exactly as David Cameron proposes to do it. By charm and moderation. Of his charm and handsome appearance, there are many contemporary accounts. William III himself called Shrewsbury “the king of hearts”, the curmudgeonly Dean Swift said that he was “the finest gentleman we have” and at another time “the favourite of the nation”. Bishop Burnet, whom I always like to quote, wrote that he had “a sweetness of temper that charmed all who knew him”.

Women loved him. He was a political moderate. He was decisive when the revolutionary situation required it, but was one of those politicians who stand above parties, and are seen as relatively non-partisan. According to one of his early biographers: “King William used to say that the Duke of Shrewsbury was the only man of whom the Whigs and Tories both spoke well.”

In his career Shrewsbury helped to make a Whig settlement of our constitution, but for Tory reasons. David Cameron is a Tory with a liberal streak; it is the same combination – it seems to run in the family. The duke, of course, was even younger; he became First Minister at the age of 28.

The letter that saved Parliament

DANIEL HAHN rereads the letter that betrayed the 1605 plotters and asks who wrote the words that prevented the fuse from being lit

It’s not much to look at – a scrap of paper with a few quick lines, unsigned. It’s nothing grand or formal, there’s no seal or signature flourish; just 160 words or so, handwritten, on a yellowed page, a little smaller than A4. But though it’s barely known today, document SP 14/216 (2) has, arguably, more mystery and more immediacy than anything else in the vast National Archives collection, and is the trigger for one of the most engaging hypotheticals in British history: what if the Gunpowder Plot had succeeded?

The Monteagle Letter takes its popular name from William Parker, Lord Monteagle, the man who on 26 October 1605 had his dinner interrupted by a servant bearing this mysterious missive. The letter spoke of “a great blow” that Parliament would receive, and advised Monteagle to absent himself; it referred to “the love that I bear to some of your friends”. It rejoiced in the thought that the bloodshed was deserved, and planned not just by man but also by God.

Monteagle was a Catholic, or had been once; the priest Oswald Tesimond described him as “a Catholic at least according to his innermost convictions”. He had this same summer written a letter to chief plotter Robert Catesby expressing his discontent at the standing of Catholics under the new regime. Besides this, Monteagle had very lately been imprisoned for his involvement in the Essex Rebellion. Although his status in court had lately been on the ascendant, he was perpetually under suspicion, so he greatly appreciated the chance to prove his loyalty to the King. He didn’t lose a moment, leaving his fellow diners and rushing the letter to Whitehall, to Secretary of State Robert Cecil.

The King was out of town on a hunt, but on his return a few days later Cecil passed the letter on to him. The “divinely illuminated” James brilliantly deduced (from the word “blow” and the reference to burning) that the letter was warning of a plot to blow up Parliament. Cecil had surely worked out the barely hidden meaning long before, but was never one to miss an opportunity to flatter the vain King and so complimented him most enthusiastically on his God-sent inspiration and his incisive intelligence. And of course they were correct: there was indeed a plot to blow up Parliament, on 5 November. Cecil ordered a search of the rooms under the Parliament chamber – revealing 36 barrels of gunpowder and a startled Guy Fawkes.

This much, at least, we know. The rest, as they say, is history; but of course history is never so simple.

With his network of informers intercepting correspondence across the Continent, it may be that Cecil knew of the plot long before Monteagle rushed into his audience clutching the tip-off. But if Cecil didn’t know, or didn’t know for sure, if he had any doubts at all – then this old page now in the National Archives can be credited with preventing an extraordinary coup, an incomprehensibly audacious, ambitious attempt to eliminate monarchy and government and all establishment, and replace it with… who knows? A Catholic England?

So to the letter itself. The writing has certainly been disguised. The hand is clumsy, but deliberately so – it’s easy enough to see places where it has been altered to hide the writer’s natural style. The prose and the vocabulary, meanwhile, are sophisticated. If we were meant to be fooled by the hand into thinking this the work of some barely literate servant, the words belie this.

Prime suspect for writing the letter has always been Francis Tresham, the plotters’ last recruit, enrolled mainly for his recently inherited wealth. From the moment he joined the inner circle of plotters, Tresham had expressed his doubts about the justification for such massive loss of life, questioning whether, for instance, the Catholics in Parliament shouldn’t be saved. And Tresham’s sister Elizabeth was married to Lord Monteagle; does the wording in the letter – “some of your friends” – refer to Monteagle’s wife? Circumstantial evidence aplenty, then. And indeed, suspicion fell on Tresham from the start. Catesby and another plotter Thomas Wintour summoned him to meet them at once; these two dedicated men were quite prepared to kill their friend for his betrayal.

And yet somehow Tresham was able to win them round. Whatever he said, whatever oaths he swore, Catesby and Wintour left the meeting convinced that Tresham was no traitor. And Catesby was not a man easily fooled. Maybe it wasn’t Tresham, then? After the failure of the plot Tresham spent weeks in the Tower of London signing statements, writing letters to Cecil, insisting that he’d opposed the plot all along and even offering assistance with the investigation – and yet never does he mention the letter. Odd, isn’t it? And besides, the tone of the letter does seem convinced by the righteousness of the plot and doesn’t sound like the voice of a waverer. But if not Tresham, then who?

Unusual suspects

There are at least as many possibilities as there were plotters. And no wonder there was a weak link. With so many men involved in the Gunpowder Plot – an unfortunate 13 – it would have been impressive if there had not been at least one Judas. And we mustn’t assume that the letter was necessarily the work of one of them. Couldn’t a devious Monteagle have written it himself? If he’d suspected something was afoot and feared he would be implicated (he knew many of the conspirators, after all), such a letter would be a fine way of preventing the plot, demonstrating his innocence, and proving his allegiance to the King, at a stroke. He did after all do extremely well out of the whole situation – earning the gratitude and trust of James and Cecil, along with a generous pension, and even a poem by Ben Jonson in his honour.

Many historians have suggested something more Machiavellian still, that a well-informed Cecil wrote the letter himself (or had one of his many shady functionaries do it). This would be an excellent way of officially “discovering” the plot without having to reveal any of his sources – let the plotters entangle themselves in their scheme while you remain in apparent ignorance, and then swoop in and save the day – there’s even a contemporary woodcut of the letter being delivered from God by an eagle. Just the sort of political theatre that came easily to Robert Cecil. As an added bonus it’s a useful way of testing Monteagle too – have the letter delivered, and if it’s not back in your hand by nightfall you know the man is no friend of the King’s. And yet… And yet there are countless other possibilities. Was it Catesby’s cousin Anne Vaux? Or consipirator Thomas Percy (as Monteagle suggested)? Or Monteagle’s sister, Mary? And so many other questions, too…

Among those who enjoy these things, the argument will continue to rage. In another four centuries we’ll still be questioning what it is we’re dealing with – a tip-off to blow the plotters’ cover, a planted excuse to officially discover an open secret, an attempt to save a friend, a test of loyalty? We’re sure that the letter exists, we know what it says, when it was delivered and to whom. And all the rest? Well, the rest is mystery. Historians have the luxury of doubt, of argument and counterargument, which is what makes it such fun after all.