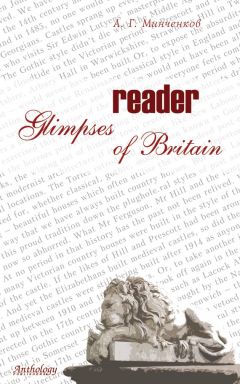

Текст книги "Glimpses of Britain. Reader"

Автор книги: Алексей Минченков

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +12

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 10 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 2 страниц]

Why I’ll keep on riding to the rescue of Blenheim

By John Spencer Churchill,

11th Duke of Marlborough

The Mail on Sunday, August 8, 2004

Running a stately home today is very much a business – that’s the way it has to be. It has to be well thought-out, well organised and well run. It’s something we have developed over a period of time and will continue to do so.

The first paying visitors were admitted to the house in 1950. In those days, we opened only four days a week. Then I managed to persuade my father to open for five days a week. When I took over in 1972 I realised we had to be open seven days a week.

Recently we increased the number of days that we’re open by extending the season – this improves the bottom line. We have to open more days because the expenses are going up all the time. This year, for example, we’re staying open until December 12 – and will re-open next year in February.

It worries me slightly that we’re opening this long because the only way you can keep a house in good tip-top order is to close it down for a certain number of weeks so you can give it a proper spring clean. Maintenance is crucial because the future of the house is all-important.

Now it is in quite good order, something I can say with pride and satisfaction. But there is a lot of stone work that needs replacing and we also have to replace the six statues that used to be on the roof. We haven’t been able to do a lot of restoration over the past four years because all the monies have been drawn to rewiring, costing hundreds of thousands of pounds. If John Churchill were to return here today I think he would be delighted to see that the place is still in reasonably good nick. The other thing is that one has constantly got to think of other means of attracting outside events. It’s no use sitting back and thinking you can carry on the business in the same way that it was done 25 years ago. There’s a lot of outside competition now.

The one thing that has really hit the stately homes business quite badly is Sunday opening. There has been a huge change to the way of life in this country on Sundays. Fifteen to 20 years ago there was very little that people could do on Sundays except visit a stately home. The shops were shut, no race meetings took place. That’s all changed.

So we have to keep innovating. This year we have restored the Secret Garden, a treasure that has remained hidden for more than 30 years.

The garden was conceived by my father, the 10th Duke, and work began in 1960 on creating a romantic and secluded haven which broke away from the formal nature of traditional Victorian gardens.

My father was a keen gardener and planted unusual species of trees, shrubs and flowers to create a Four Seasons garden comprising winding paths, soothing water features, bridges, fountains, ponds and streams.

Over the past 30 years, the garden has grown wild and remained inaccessible to all but the most intrepid of explorers. However, a team of dedicated gardeners set about restoring it to its former glory.

We are constantly having to come up with things to make people aware that there is more to Blenheim than just the house.

At our music festival this year, for example, we had Barry Manilow performing on the final night. I’m a great Barry Manilow fan – he’s performed here before and I know him quite well.

You have to cater to all sections of the community, especially children, because they quite often tell the parents what they’ll be doing at weekends.

If anybody is interested in history or heritage then automatically they’ll want to come to Blenheim. Here, you will find not just the history of our family but to some extent an insight into the history of Britain since the 1700s.

Our special exhibition on the Battle of Blenheim explains just how important that victory was. If the French had won they would have dominated the world – the Americans might well have ended up speaking French.

Whenever I’ve been away from home, it is still a great thrill to return. I love seeing the house again as I come down the drive but I also have a nagging anxiety: “What new problem is there now to fix?”

My Favourite Room

It has to be that incredible room the Long Library – it’s 180ft long and was designed by Vanbrugh as a picture gallery. The room’s proportions are amazing.

From here you look out over the Water Terrace Gardens laid by my grandfather down towards the lake. It’s a very big room. It needs quite a lot of people in there, say 300, to make you realise just how big.

My Favourite Painting

I would choose that 1905 painting of my grandfather and grandmother by John Singer Sargent. The painting hangs in the Red Drawing Room and shows my father standing between his father Charles, the 9th Duke, and his mother Consuelo with the Blenheim spaniels. It’s quite magnificent – a wonderful composition.

My Favourite View

That first glimpse of the house as you come down the drive from Woodstock has been described as “the finest view in England”. You have the towers of the palace to the left, to the right is the Column of Victory with its statue of the 1st Duke of Marlborough and in front is the great lake with Vanbrugh’s Grand Bridge. When George III saw this view he exclaimed: “We have nothing to equal this!”

My Favourite Ancestor

I have a particular affection for my cousin Sir Winston Churchill who was born here on November 30, 1874. He proposed to his wife Clementine in the Temple of Diana and was buried near Blenheim Palace in the church at Bladon near his mother and father.

We have an excellent exhibition about Sir Winston near the room where he was born. The letters to his father are fascinating.

Winston was a great friend of my grandfather, and my father and mother. He was my godfather and I knew him quite well. He loved Blenheim. One of his biggest works was the four-volume biography of the 1st Duke.

It was very moving that he made the decision to come back here to be buried. On January 30 1965, I was fortunate enough to travel on the train which brought his body from Waterloo down to the station at Long Hanborough near Bladon. It was the most amazing day, nobody has ever seen a day like it.

Sex war

by Melanie Phillips

Daily Mail, March 29, 2003

The violence swept the country. Windows and street lamps were smashed, the cushions of train carriages slashed, phone wires severed, golf greens burned with acid and buildings razed to the ground. Thirteen paintings were hacked to bits in a Manchester art gallery and bombs were placed near the Bank of England.

Senior politicians were ambushed and assaulted. A package containing sulphuric acid was sent to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and burst into flames when opened. An attempt was made to burn down his country home.

Even the Prime Minister was a target. On a golf links in Scotland, attackers tried to tear off his clothes and were prevented from doing so only by the intervention of his daughter, who protected him with her fists.

On another occasion, an axe was thrown at the Premier. It missed him, but grazed the ear of an MP sitting alongside.

Britain had never seen anything quite like it. And the most shocking thing of all was that every one of these outrages was perpetrated by women.

They were the suffragettes – a term first coined by the Daily Mail to describe the militant activists who crusaded for female suffrage, or the right to vote, in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Today, these women are widely regarded with uncritical veneration; their cause so manifestly just, and their one-time opponents so manifestly wrong, that their status as modern heroines goes unchallenged.

Last year, Emmeline Pankhurst, their radical leader, was put by BBC viewers near the top of a list of the 100 Greatest Britons of all time. Her statue stands outside the Houses of Parliament.

But the story of the suffragettes – or at least, the most militant among them – is much stranger than most people realise. Far from being a simple battle for equality at the ballot box, their campaign was driven by a deep-rooted distaste for male sexuality.

Quite simply, the more extreme suffragettes were man-haters, waging what amounted to a sex war. They regarded men as a lower form of life, whose untrammelled sexual appetites were the root of all evil – from physical disease to every kind of moral degeneracy.

For these women, winning the vote was merely a means to an end: the reining in of male lust, which they thought would raise the whole of society to a higher spiritual plane.

What is more, they were prepared to adopt virtually any tactics to achieve it – even those we would now call terrorism.

The explanation for this sexual fervour lies in the squalid world of Victorian vice, with its huge and highly visible trade in prostitution. In 1841 the Chief Commissioner of Police estimated there were 3,325 brothels in Central London alone.

Thirty years later, a French visitor to the East End reported that “all the houses, except one or two, are evidently inhabited by harlots”. According to Scotland Yard’s director of CID, it was impossible for a respectable woman to walk through the West End in mid-afternoon because of the number of prostitutes openly soliciting.

Droves of girls were seen huddling along Regent Street, Piccadilly and Haymarket, urinating and defecating in public. For men of such tastes, children were easily procured: the age of consent was just 12.

Domestic servants joined the trade at night, desperate to supplement their meagre wages. Shop assistants did the same, with the encouragement of West End dress-shop managers who hired out clothes to them by way of advertising.

The phenomenon gave rise to endless scandalised discussion. At first, conventional opinion held that the prostitutes were corrupting the nation’s morals, whereas the men who patronised them were merely satisfying their natural inclinations while leaving respectable women unsullied. Gradually, however, the climate changed. Under the influence of evangelical reformers, the public began to see prostitutes as victims exploited by profligate males.

Rescuing “fallen women” became a national pastime. Reformers would seek out girls in the streets, give them improving tracts and plead with them to change their ways. The Liberal leader William Gladstone frequently took prostitutes home, where his wife gave them food and shelter.

But compassion was mixed with a morbid fear of venereal disease, which was especially rife among the Armed Forces. One in three cases of sickness in the Army was due to VD.

MPs responded by passing the Contagious Diseases Acts, which allowed police to arrest suspected prostitutes within a ten-mile radius of garrison towns, hold them for several days and order them to undergo an internal examination with a speculum.

The results were deeply unpleasant. Women, not always prostitutes, could have their most intimate privacy invaded, often brutally, on the say-so of a single policeman.

For many women, it crystallised the feeling that they and their kind were being victimised when the real fault lay with amoral men looking for sex. When doctors tried to extend the legislation nationwide in 1869, there was uproar.

Under the leadership of a charismatic clergyman’s wife, Josephine Butler, women across the country banded together to campaign for the law’s repeal. It was 16 years before they succeeded, but the crusade had far-reaching effects.

Butler and her colleagues saw their job as the reform of promiscuous men as much as the rescue of fallen women. In their eyes, it was men who funded prostitutes, and men who passed the laws degrading them.

The only solution was for women to enter public life and sort things out. “Male vice” would only end if women had the vote and the chance to purify politics.

It proved a popular rallying cry. Women’s emancipation became a crusade to save humanity from men’s corrupting influence. The battle for the vote became inextricably tangled up with a campaign for sexual purity.

The year 1886 saw the final repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act. It was a watershed in the women’s movement. Feminists redoubled their demands for the vote and became ever more outspoken in their attacks on men. To some extent, this was a natural reaction to the horrors they had uncovered. In part, however, it arose from a sense of moral superiority that was rapidly tipping over into puritanical self-righteousness.

The most militant now argued that marriage was as exploitative as prostitution – just another way of purchasing women. Some saw all sexual relations with men as abhorrent. Women like the veteran feminist Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy believed that male sexuality was an expression of the bestial side of human nature, and that to indulge it threatened the very existence of society.

Indeed, she considered that nearly all “diseases of woman” – including, bizarrely, menstruation – were due “to one form or other of masculine excess or abuse”.

This man-hating agenda encouraged a move towards sexual separatism, with many campaigners turning their backs on marriage and remaining defiantly single. At the time, they were simply called spinsters; in many cases, we would now consider them to have been lesbians.

In an atmosphere of growing fundamentalism, the hardliners were in the mood for open revolt. All that was needed was a suitably reckless and fanatical leader to show the way.

This is where Emmeline Pankhurst came in. She and her equally formidable daughter, Christabel, would take the sex war to a new level.

Raised in Manchester but educated in Paris, Emmeline was strikingly beautiful, yet her ambition and ruthlessness were evident from the start.

“She should have been a lad,” said her father. He meant it as a compliment, but she heard him “with rebellion in her heart”.

Ironically, she inherited the cause of women’s liberation from her husband, Richard Pankhurst, a failed politician who in 1870 had drafted the first women’s suffrage bill to be put before Parliament. After his death, she set up her own movement called the Women’s Social and Political Union. Such was her personal magnetism that disciples flocked to her like bees to honey. In time, hero-worshipping crowds would throw jewels and watches at her feet.

Her daughter Christabel was even more charismatic and became the pin-up of the suffragette cause. Slender, graceful, and with “the flawless colouring of a briar rose”, she was physically enchanting to men and women alike.

But like her mother, Christabel was utterly ruthless. “In spite of her charm and feminine attraction,” wrote one admirer, “there was in her soul a core as hard and brilliant as steel, and I sometimes thought as pitiless.”

It was Christabel who established the suffragettes’ strategy of deliberately courting martyrdom to win the propaganda war. In 1905, after disrupting a political meeting, she and a colleague spat at a policeman and refused to pay the fine, ensuring they were sent to jail.

She and Emmeline then encouraged their supporters to follow suit, and milked every drop of publicity when they were punished.

Some of the protests were little more than stunts. Burning rags were stuffed into letterboxes, keyholes blocked with lead, chairs flung into the Serpentine, flower beds damaged, and envelopes containing red pepper and snuff sent to every Cabinet minister.

But as we have already seen, there was also real violence – with repeated attempts to assault the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. Amid police reports of suffragettes practising with revolvers, there were even fears he might be assassinated. On one occasion, his car was forced to slow down to avoid a woman lying in the road. Other women promptly jumped out and belaboured him over the head with dog whips, his head protected only by his top hat.

Many of the suffragettes jailed for such attacks won further celebrity by going on hunger strike. The Government introduced force-feeding, inserting tubes through their noses and down their throats while warders held them down.

It was exactly what the Pankhursts wanted. They intended their violence to provoke an extreme reaction and produce the impression of innocent women being persecuted by an oppressive state.

Harsh though the word may seem, such manipulative cynicism is the hallmark of terrorism. Worse still, the suffragette leaders washed their hands of any responsibility for the followers they lured into violence.

It was an act of monstrous cowardice that made victims of the very women they were purporting to lead to liberation. But such tactics were typical of the Pankhursts, who ran their movement in autocratic style and cast out any colleagues who dared to voice dissent.

Both women adored the limelight and the opportunity it gave them to strike melodramatic poses. They shared a pathological self-importance and gloried in their chosen role as martyrs.

Christabel, however, spoilt the effect by running away to Paris in 1912 to avoid further risk of being jailed. There she spent her time sightseeing and visiting fashionable shops, while encouraging those she had left behind to launch a campaign of arson.

In truth, these militant tactics were counter-productive and merely made the Government more resistant to reform. The Pankhursts’ response was to crank up the idea of the war against male lust. Stone-throwing, arson and physical attacks, argued Emmeline, were all a means of cleansing society – the only way to eradicate the “Social Evil” of prostitution.

“As a result of the Social Evil,” she thundered, “the nation is poisoned morally, mentally and physically. Women are only just finding this out.” “As their knowledge grows, they will look upon militancy as a surgical operation – a violence fraught with mercy and healing.”

Puritanism of the rich

by George Monbiot

The Guardian, November 9, 2004

“If Bush wins,” the US writer Barbara Probst Solomon claimed just before the election, “fascism is possible in the United States.” Blind faith in a leader, she said, a conservative working class and the use of fear as a political weapon provide the necessary preconditions.

She’s wrong. So is Richard Sennett, who described Bush’s security state as “soft fascism” in the Guardian last month. So is the endless traffic on the internet.

In The Anatomy of Fascism, Robert Paxton persuasively describes it as “… a form of political behaviour marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy and purity”. It is hard to read Republican politics in these terms. Fascism recruited the elite, but it did not come from the elite. It relied on hysterical popular excitement: something which no one could accuse George Bush of provoking.

But this is not to say that the Bush project is unprecedented. It is, in fact, a repetition of quite another ideology. If we don’t understand it, we have no hope of confronting it.

Puritanism is perhaps the least understood of any political movement in European history. In popular mythology it is reduced to a joyless cult of self-denial, obsessed by stripping churches and banning entertainment: a perception which removes it as far as possible from the conspicuous consumption of Republican America. But Puritanism was the product of an economic transformation.

In England in the first half of the 17th century, the remnants of the feudal state performed a role analogous to that of social democracy in the second half of the 20th. It was run, of course, in the interests of the monarchy and clergy. But it also regulated the economic exploitation of the lower orders. As RH Tawney observed in Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1926), Charles I sought to nationalise industries, control foreign exchange and prosecute lords who evicted peasants from the land, employers who refused to pay the full wage, and magistrates who failed to give relief to the poor.

But this model was no longer viable. Over the preceding 150 years, “the rise of commercial companies, no longer local, but international” led in Europe to “a concentration of financial power on a scale unknown before” and “the subjection of the collegiate industrial organisation of the Middle Ages to a new money-power”. The economy was “swept forward by an immense expansion of commerce and finance, rather than of industry”. The kings and princes of Europe had become “puppets dancing on wires” held by the financiers.

In England the dissolution of the monasteries had catalysed a massive seizure of wealth by a new commercial class. They began by grabbing (“enclosing”) the land and shaking out its inhabitants. This generated a mania for land speculation, which in turn led to the creation of sophisticated financial markets, experimenting in futures, arbitrage and almost all the vices we now associate with the Age of Enron.

All this was furiously denounced by the early theologists of the English Reformation. The first Puritans preached that men should be charitable, encourage justice and punish exploitation. This character persisted through the 17th century among the settlers of New England. But in the old country it didn’t stand a chance.

Puritanism was primarily the religion of the new commercial classes. It attracted traders, money lenders, bankers and industrialists. Calvin had given them what the old order could not: a theological justification of commerce. Capitalism, in his teachings, was not unchristian, but could be used for the glorification of God. From his doctrine of individual purification, the late Puritans forged a new theology.

At its heart was an “idealisation of personal responsibility” before God. This rapidly turned into “a theory of individual rights” in which “the traditional scheme of Christian virtues was almost exactly reversed”. By the mid-17th century, most English Puritans saw in poverty “not a misfortune to be pitied and relieved, but a moral failing to be condemned, and in riches, not an object of suspicion… but the blessing which rewards the triumph of energy and will”.

This leap wasn’t hard to make. If the Christian life, as idealised by both Calvin and Luther, was to concentrate on the direct contact of the individual soul with God, then society, of the kind perceived and protected by the medieval church, becomes redundant. “Individualism in religion led… to an individualist morality, and an individualist morality to a disparagement of the significance of the social fabric.”

To this the late Puritans added another concept. They conflated their religious calling with their commercial one. “Next to the saving of his soul,” the preacher Richard Steele wrote in 1684, the tradesman’s “care and business is to serve God in his calling, and to drive it as far as it will go.” Success in business became a sign of spiritual grace: providing proof to the entrepreneur, in Steele’s words, that “God has blessed his trade”. The next step follows automatically. The Puritan minister Joseph Lee anticipated Adam Smith’s invisible hand by more than a century, when he claimed that “the advancement of private persons will be the advantage of the public”. By private persons, of course, he meant the men of property, who were busily destroying the advancement of everyone else.

Tawney describes the Puritans as early converts to “administrative nihilism”: the doctrine we now call the minimal state. “Business affairs,” they believed, “should be left to be settled by business men, unhampered by the intrusions of an antiquated morality.” They owed nothing to anyone. Indeed, they formulated a radical new theory of social obligation, which maintained that helping the poor created idleness and spiritual dissolution, divorcing them from God.

Of course, the Puritans differed from Bush’s people in that they worshipped production but not consumption. But this is just a different symptom of the same disease. Tawney characterises the late Puritans as people who believed that “the world exists not to be enjoyed, but to be conquered. Only its conqueror deserves the name of Christian.”

There were some, such as the Levellers and the Diggers, who remained true to the original spirit of the Reformation, but they were violently suppressed. The pursuit of adulterers and sodomites provided an ideal distraction for the increasingly impoverished lower classes.

Ronan Bennett’s excellent new novel, Havoc in its Third Year, about a Puritan revolution in the 1630s, has the force of a parable. An obsession with terrorists (in this case Irish and Jesuit), homosexuality and sexual licence, the vicious chastisement of moral deviance, the disparagement of public support for the poor: swap the black suits for grey ones, and the characters could have walked out of Bush’s America.

So why has this ideology resurfaced in 2004? Because it has to. The enrichment of the elite and impoverishment of the lower classes requires a justifying ideology if it is to be sustained. In the US this ideology has to be a religious one. Bush’s government is forced back to the doctrines of Puritanism as an historical necessity. If we are to understand what it’s up to, we must look not to the 1930s, but to the 1630s.

Внимание! Это не конец книги.

Если начало книги вам понравилось, то полную версию можно приобрести у нашего партнёра - распространителя легального контента. Поддержите автора!