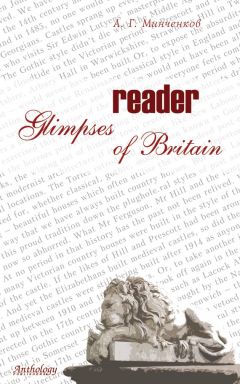

Текст книги "Glimpses of Britain. Reader"

Автор книги: Алексей Минченков

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +12

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 10 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 2 страниц]

Spencer rejected Diana’s plea for home, letters reveal

by Caroline Davies

The Times, October 21, 2002

EARL Spencer turned down a request from his sister, Diana, Princess of Wales, for a home on the family’s Althorp estate just six months after her separation from the Prince of Wales, according to private letters read to a jury yesterday.

Three letters found at the home of the Princess’s former butler, Paul Burrell, show she was rebuffed by her brother who feared her presence would cause too much disruption to his family.

The issue caused a rift between the two, leading Lord Spencer to return one of the Princess’s letters unopened. The correspondence, found in a bench in the study at Burrell’s Cheshire home, centred on the Princess’s desire to move to the Garden House, on the estate where she had been raised as a child, and which her brother had inherited.

Burrell, 44, denies three charges of theft, involving 310 items he is alleged to have taken from the late Princess’s Kensington Palace apartment.

Dated in June 1993, and read aloud to the Old Bailey by Lord Carlile, QC, defence counsel for Burrell, the first letter begins “Dearest Duch”, the earl’s pet name for his sister, and is signed “Carlos”, her nickname for him. In it he writes: “I thought I should update you on the Garden House and keep you informed of developments. I am keen to have everything sorted out clearly in advance of any decision, so there are no problems if the whole thing goes ahead.

“I see your clear need for a country retreat and I am happy to help provide it as long as there is not too much disruption to us or to the estate.

“The Garden House seems to suit your needs perfectly. It has been previously let for Ј20,000 a year, although I don’t ask for as high rent from you, but for Ј12,000 to include cleaning inside and lawnmowing and tidying up outside, on the basis of one day a week cleaning and half-a-day gardening.

“All in all there is a lot of room for conflict if everything is not sorted out in advance. I am sorry to be so businesslike about it, but it is vital that it is all sorted out now.

“I have to look after Victoria and the girls first and therefore it is my responsibility that their privacy and quality of life is not undermined by your moving in. I thought it best to bring it all up before the police got involved, in case you decide to pull out.”

Two weeks later, however, Lord Spencer had a change of heart. “Dearest Duch,” he wrote, “I am sorry but I have decided that the Garden House is not a possible move. There are many reasons, most of which centre on the inevitable police and press interference that will follow.”

He adds that he is now employing a senior agent and the property is needed for him to live in. “I know you will be disappointed but I know I am doing the right thing for my wife and children. I am just sorry I cannot help my sister!

“Seriously though, there are farmhouses around here that may well not interfere with us, but I cannot afford to give them rent free although I wish I could. In theory it would be lovely to help you out and I am sorry I can’t do that. Victoria and I really value our privacy and the combined pressure of the police, neighbours and friends have definitely compromised that.

“If you are really interested in renting a farmhouse, either here or in Warwickshire or Norfolk, that would be wonderful.” The third letter, on June 28, shows the rift had developed, when Lord Spencer replied to a letter from the Princess with the words: “Dearest Duch, Knowing the state you were in the other night when you hung up on me, I doubt whether reading this will help our relationship. Therefore I am returning it unopened because it is the quickest way to rebuild our friendship.” He signs off with: “Have a very happy birthday on Thursday, Love Charles.”

£ 100,000 price on miniature head of Lord Damle

by John Vincent

The Times, March 11, 2000

He was, according to Mary Queen of Scots, “the lustiest and best-proportionit lang man” she had ever seen.

Lord Darnley’s physical attractions, however, served only to paper over his woeful moral and mental weaknesses.

Two years after the couple’s controversial wedding in Edinburgh, Darnley was murdered following his involvement in the murder of the Queen’s private secretary, David Rizzio.

Now, after more than 400 years, an exquisite portrait miniature of the spoiled, arrogant and vain nobleman who became King of the Scots has surfaced from a private collection.

The tiny picture showing a teenage Darnley, clad in yellow doublet and white ruff, is attributed to Levina Teerlinc, the most prominent miniaturist of the period.

Surrounded by an elaborate enamelled frame, the rare portrait of the descendant of Henry VII is expected to fetch up to Ј100,000 when it goes on sale at Bonhams next Thursday.

Claudia Hill, a Bonhams specialist, said yesterday: “It is an extremely important portrait from a period when not only were very few miniatures produced, but those that were painted were confined to the royal entourage.

“Levina Teerlinc was the most prominent limner of the period, serving four monarchs from Henry VIII’s later years until well into Elizabeth I’s reign.

“The miniature, which is dated 1560, was, of course, portable and may have been secretly transported to Mary in prison,” added Miss Hill.

Lord Darnley was born in December 1545, the eldest son of the Earl of Lennox. Through his mother, a Douglas, he was descended from Henry VII.

In 1565, aged 19, he married the 22-year-old Mary Queen of Scots at Holyrood Palace to become King of the Scots. Their only child was a son, who became James I of England and VI of Scotland.

Not only were they cousins and Catholics but, as great-grandchildren of Henry VII, both had claims to the English throne. But Mary was infatuated with Darnley, deaf to warnings about the political consequences.

Mary was held prisoner in Scotland but escaped to England, where she was imprisoned by Elizabeth I for 19 years before being executed at Fotheringhay Castle on Feb 8, 1587.

Darnley died when an explosion destroyed a house in Edinburgh. It is believed that he and his servant had already been strangled.

How the king was thwarted from making plea to natio

by Alan Hamilton

The Times, January 30, 2003

Being summoned to the back gate of Buckingham Palace under cover of darkness and ushered into the royal presence through a window may have been the last straw for the Prime Minister. But Stanley Baldwin was already determined that the King would not make the broadcast that he wanted to.

Documents released by the Public Record Office today detail Edward VIII’s final and futile attempt to bypass the opposition of Baldwin’s Government to his marrying Wallis Simpson, and appeal directly to the people.

With the help of Winston Churchill, then a Conservative backbencher, the King had drafted a speech that he proposed to deliver on BBC radio on December 4, 1936. In it, he was to announce his intention of marrying the twice-divorced American – the subject of rumour in foreign, hut not British, newspapers.

In the draft speech, Edward offered to leave the country for a spell after the marriage to allow the fuss to die down, but he made no mention of abdication. He clearly still hoped to contract a marriage, even a morganatic one, and retain his place on the throne.

He summoned Baldwin to discuss the planned broadcast in secret. The Cabinet papers of the day record the Prime Minister’s arrival.

“On 3 December Baldwin was summoned to the Palace by the King’s Valet to come secretly at 9pm. He had been driven there and taken in by a back entrance; but all the same he had been photographed. Then he had been introduced through a window.”

Next day, Baldwin gave his unequivocal answer to the King: it would be a grave breach of constitutional principles if the King were to broadcast a statement on a matter of public interest without the advice of his ministers, both in Britain and the Dominions.

“If he does it without advice, he ceases to act as a constitutional monarch, and his intervention is calculated to divide his subjects into opposing camps. It is manifest that the King’s broadcast must have this result.”

Baldwin, becoming more determined by the day that the King should go, offered a further raft of objections to the broadcast: “It would shock many people – especially womenfolk where sentiment for the monarchy is so strong – to hear directly from the King of his intention to marry a woman who is still another man’s wife.”

The Prime Minister listed other objections: it would lead to adverse press comment on Mrs Simpson and her antecedents; it would encourage intervention in the divorce proceedings and could lead to a physical attack on Mrs Simpson; and the proper place for such an announcement was in the parliaments of Britain and the Dominions.

“The proposed course would be regarded as an affront to the Governments and parliaments of the Empire,” Baldwin concluded. Such a broadcast could be made only on the advice of the King’s ministers, “who would be responsible for every sentence in it”.

That evening, one of the King’s dinner guests was Winston Churchill, who on December 5 wrote to Baldwin pleading that the King be shown “kindness and chivalry” to help him to solve his dilemma.

Churchill’s letter, released for the first time today, warned the Prime Minister of the King’s mental state.

“I strongly urged his staff to call in a doctor. His Majesty appeared to me to be under the greatest strain and to be near breaking point.

“He had two marked and prolonged blackouts in which he completely lost the thread of his conversation. Although he was gallant and debonair at the outset, this soon wore off and his mental exhaustion was painful to see.”

Churchill went on: “I told the King that if he appealed to you to allow him time to recover himself and to consider now that things have reached their climax, the grave issues, constitutional and personal, with which you have found it your duty to confront him, you would I am sure not fail in kindness and chivalry.”

But the plea fell on deaf ears. Baldwin told the Cabinet next day that he had never found the King more cool and clear-minded. The Abdication was finally announced, as Baldwin had wished, in the Commons and other Dominion parliaments on December 10. When Edward was allowed to broadcast his farewell message on December 12, he was no longer King.

Council tax bills to rise

by Jill Sherman and Alexandra Frean

The Times, February 5, 2003

Council tax bills in England are set to rise by up to ten times the rate of inflation following Tony Blair’s decision to transfer government funds from Tory suburbs in the South to Labour heartlands in the North.

The rise, the biggest since the council tax was introduced in 1993, was condemned by the Conservatives yesterday as a stealth tax that would raise bills for ordinary families to well over Ј1,000 a year. Local government experts called the rises shocking, and said that they would put pressure on John Prescott, the Deputy Prime Minister, to reintroduce capping.

A survey carried out by The Times shows that some districts will impose council tax rises of up to 27 per cent to meet government spending commitments and local demands. The increases, following the Government’s gamble to appease core Labour voters, could jeopardise the party’s chances in this year’s council elections and further erode the Prime Minister’s popularity.

Most of the highest increases will be levied by Tory councils in the South, while many Labour authorities in the North and the Midlands have contained increases to below 10 per cent. The top rises are in London boroughs with several proposing hikes of over 23 per cent, partly owing to Ken Livingstone’s mayoral levy. But county councils such Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Devon and Suffolk have all approved increases of 17 to 20 per cent.

The average increase in outer London is 19.2 per cent, bringing the Band D council tax to Ј1,165.90. In inner London the average increase is 15.9 per cent, giving a Band D tax of Ј1,030.07. The average rise in metropolitan boroughs is 8.8 per cent with the Band D tax at Ј1,094.12.

The average increase in County Councils is 13 per cent bringing the Band D rate to Ј873.46. For district councils there is an average rise of 13.6 per cent giving a Band D rate of Ј1,126.77 and for unitary councils the average rise is 10.9 per cent and the average Band D tax is Ј1,014.63.

The increases are highest in councils that do not have local elections this year, suggesting that many may have kept taxes down last year when they faced the polls. Experts also suggested that councils have taken the chance to inflate bills at a time when they could blame the Government for its decision to reform funding allocations. “These are socking great increases,” Tony Travers, local government expert at the London School of Economics, said. “If I was the Government I would be horrified, and it will undoubtedly put pressure on the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister to cap the increases.”

Mr Travers said that the proposed bills would damage the Government’s reputation as a low-tax administration as well as its efforts to court the middle classes before this year’s local elections.

Last autumn Tony Blair made the decision to appeal to core voters who had become increasingly disgruntled with Labour’s failure to address the North/South divide. Mr Prescott introduced a radical review of local government funding that penalised the South to give more to the North.

Kensington Palace

The Daily Telegraph

Plans by the Queen to turn Kensington Palace into a “people’s palace” are not inappropriate for a building that was never intended to be a front-line royal showpiece.

The Jacobean mansion began its days as the home of Sir George Coppin, a wealthy landowner, and was known simply as Nottingham House on its completion in 1605.

It became a royal residence 93 years later when its situation in the village of Kensington attracted the asthmatic William III and his Queen Mary. They bought it for Ј14,000.

Although the King commissioned Christopher Wren to enlarge the building, it remained modest as palaces go. When part of the newly extended palace collapsed, there were suggestions that Wren and his assistant were too preoccupied with work on Hampton Court.

Wren’s improvements included pavilions to each corner of the house and a new courtyard and entrance on the west side. Royal apartments were built in the south-east and north-west pavilions, and the Chapel Royal and the Great Stairs in the south-west pavilion.

Royal apartments were divided in the traditional manner, between the King’s and Queen’s suites, each with its own entrance staircase. But there was no series of elaborate staterooms since the King decreed that he saw Kensington as a private residence.

Despite its relative modesty, Kensington Palace was used by successive monarchs. George II died there in his water closet. Queen Victoria was born and brought up in the palace and the most impressive rooms are those designed by George I. Victoria saved the palace when it fell into disrepair in the second half of the 19th century. She talked of her love for her childhood home even though if had been “a rather melancholy childhood in the modest palace, the rooms of which were dreadfully dull, dark and gloomy”.

George V once said he wanted to pull down Buckingham Palace and, with the money saved, rebuild Kensington on a grander scale as the main town residence, a wish never to be fulfilled.

While the public has had access to the State apartments on the north side – these were first occupied by Mary II – and to the ground floor with its Court Dress Collection, the rest of the building contains the “grace and favour” private apartments of royals and their staff.

Currently living there are Princess Margaret, Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, Duke and Duchess of Kent and Prince and Princess Michael of Kent.

The grace and favour apartments were the subject of controversy in the past. In July 1994, there were protests from Labour MPs when two officials moved into a pair of apartments being refurbished as part of repairs costing the taxpayer more than Ј750,000.

One apartment had five bedrooms, four bathrooms, a sitting room, dining room, study, kitchen and utility room, basement room and two separate lavatories.

The other had four bedrooms, two bathrooms, sitting room, dining room, a study, kitchen and utility room, basement room, shower room and separate lavatory.

Later Buckingham Palace said the officials had each taken a big pay cut because of their accommodation.

If the palace eventually houses the British Royal Collection, it will provide a fitting home for what has been described as one of the greatest private art collections on Earth, rivalling the Vatican.

Held in trust by successive monarchs, it contains more than 7,000 paintings, 3,000 miniatures, 30,000 Old Master drawings and watercolours, 500,000 engravings and etchings and hundreds of thousands of other works.

The collection, housed across the country’s royal castles, palaces and estates, reflects the personal tastes of sovereigns over five centuries, from the Tudors to the present day. Its sheer size and diversity has discouraged attempts even to estimate its worth.

Among the paintings are masterpieces by Bruegel, Rubens, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Gainsborough and Canaletto. The collection also includes one of the world’s most important collections of Sevres porcelain.

While the Queen cannot sell anything from the collection but must hand it on to her successor, she has been in favour of lending works for public exhibition. The National Gallery has 2,300 paintings from the collection.

An expert with the British Royal Collection said: “Former royal collections in countries like France, Germany, Spain and Austria were ceded to the state and became the nucleus of national collections.

“By contrast, the Royal Collection has remained intact as a private collection within buildings such as Buckingham Palace, Balmoral, Windsor Castle, Sandringham, Hampton Court Palace and Kensington Palace.”

Special agent Holbein spied on Henry VIII

by Richard Woods

The Sunday Times, May 19, 1996

Thinker, painter, socialite, spy. Hans Holbein, the great Renaissance artist who created the enduring image of stout Henry VIII, has been exposed as a secret agent deeply involved with intrigue in the king’s court.

That is the picture painted in a new book by the historian Derek Wilson, who reveals Holbein as acting as an agent for Thomas Cromwell, one of Henry’s leading ministers; Holbein reported back information gleaned from the eminent courtiers whom he painted.

The controversial study, the first significant biography of the artist for 80 years, argues Holbein also included in his paintings coded signals and propaganda about political figures of the time.

Wilson, who has approached his subject as a historian rather than an art specialist, reinterprets Holbein’s motives and paintings through the religious and political tumult of the Reformation.

“It is largely a question of getting a different focus. Many of the pictures talk about the siluation he was working in,” said Wilson, whose book, Hans Holbein, Portrait of an Unknown Man, will be published by Orion next month.

Holbein, who was born in Germany, won early success, travelled widely and came to England where he fell under the patronage of Sir Thomas More.

He returned briefly to Europe before spending the last 11 years of his life in England, rising to become the “king’s painter”. His patron then was Thomas Cromwell, who had supplanted More as the head of Henry’s government.

The patronage system was a two-way street, argues Wilson. In return for material support, Cromwell required Holbein to act as his eyes and ears among the nobility whose portraits he executed.

“Why, when he was the king’s painter, busy there and busy with Cromwell, was he also painting others outside that circle?” asks Wilson. The answer, he said, was that Holbein was seeking out commissions on Cromwell’s instruction. At the top of Cromwell’s hit-list were More and Bishop John Fisher, incarcerated in the Tower of London for refusing to follow Henry’s reformation and reject papal authority. Wilson argues that Holbein sketched Fisher while he was in the tower.

“What was going on here? How could an artist get into the tower?” asks Wilson. The answer, he says, is that Cromwell was sending agents in to talk to More and Fisher. Certainly Cromwell attempted to gather information and prove treason against More and Fisher while they were imprisoned.

Brian Sewell, the eminent art critic, said last week the thesis was “ingenious” and that Holbein’s connections would have made him an excellent spy. But he doubted the artist had the required skills. “Language is the real problem,” he said. “As far as we know Holbein never managed to learn English properly. He spoke a sort of Dennis the Dachshund English.”

But Wilson also points to clever coded signals in Holbein’s paintings. “Renaissance artists loved words, puns and hidden messages,” said Wilson.

Concealed in The Ambassadors, Holbein’s masterpiece, restored and rehung last month by the National Gallery, is a message about More. The picture shows two men standing either side of some shelves. Three elements of the painting – a dagger, one of the shelves and a wildly elongated skull – all point to one spot: one of the men’s garments. The cloth’s colour is an unusual mulberry or, in Latin, morus. The strange skull is a memento mori, a reminder of death. These two elements, said Wilson, secretly mean: remember More. A crucifix suggests the Christian faith was under threat.

Even more daringly in one painting, Holbein appears to have secretly disparaged Anne of Cleves, who was to be Henry’s fourth wife. In 1539 Holbein was in the awkward position of being sent to Europe to paint Anne’s portrait. She was a noble whom Cromwell, for his own political reasons, wanted Henry to marry.

Holbein found himself under pressure to produce a flattering portrait to take back for the king. But in truth Anne was plain and talentless and Holbein doubted that she was a suitable match. So he included a subtle message. The painting is packed with symmetry but with one omission, the jewelled bands on Anne’s skirt. One on the left is not complemented by one on the right. This, said Wilson, is meant to indicate Anne’s clumsiness.

But he argues that it goes further. In court French, trait a gauche, pas а droit means band on the left, not on the right. But it sounds like trиs gauche, pas adroit (very awkward, not skilful), which summed up Anne’s faults.

According to Sewell, visual puns and hidden messages are “precisely the kind of thing one should look for in Tudor painting”. Again he found Wilson’s interpretations ingenious, but open to question. “It is a very attractive solution: but I think it is too clever.” Holbein is not thought to have been fluent in French either.

Wilson said: “Holbein found in Cromwell a man of ideals who was going to put them into practice, and a protйgй commits himself to his patron. He was his agent. I have tried to reveal the real Holbein.”

As an agent, Holbein may have been smarter than his masters. Unlike More, Boleyn and Cromwell, the artist was not beheaded.