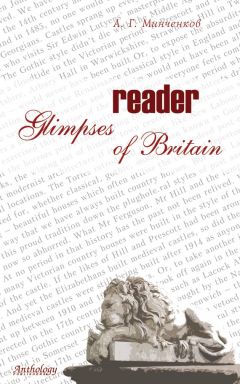

Текст книги "Glimpses of Britain. Reader"

Автор книги: Алексей Минченков

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +12

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 10 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 2 страниц]

The blood that links the greatest Britons

by Emma Soames

The Daily Telegraph, Tuesday, November 26, 2002

THE nation has decided. Sir Winston Churchill was the greatest Briton of them all. No surprise there; even those who would have preferred to see the title bestowed upon another could hardly quarrel with the final choice.

But perhaps the most extraordinary feature of the BBC poll was that members of the same family filled two of the top three places.

With Diana, Princess of Wales finishing third in the survey, the Spencer-Churchills can justifiably claim to be the nation’s most successful dynasty.

If anything, their light shines even brighter than the survey would suggest. Arguably, another family member should have been in the top 10 – John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, considered by many to have been the country’s greatest general.

He did not even make the final 100. Maybe his stunning victories across Europe during the War of the Spanish Succession are no longer learned at school.

But a case could be made to place him ahead of Nelson (9), Wellington (15) and Montgomery (88) as Britain’s most significant military figure.

Over the centuries, the combined might of the Spencers and the Churchills has been greater even than the Royal dynasties. They played a crucial role in the revolution of 1688, which banished the Stuarts, changing the succession of the monarchy.

The Spencers started out as Tudor sheep farmers and grew rich through the wool trade, reaching the upper aristocracy within 200 years. They were already installed at Althorp in 1506.

The Churchills were a family of West Country gentry whose prominence largely derived from John’s military prowess. The rewards for his victories were great: a Dukedom and one of the country’s greatest homes, Blenheim Palace. The two clans were joined when Anne Churchill, daughter of the first Duke of Marlborough, married Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland. One branch of their line inherited the Althorp and Spencer estates; the other succeeded to the Duchy of Marlborough.

In 1817, the 5th Duke of Marlborough was authorised “to take and use the name of Churchill, in addition to and after that of Spencer… in order to perpetuate in his family a surname to which his illustrious ancestor John, 1st Duke of Marlborough, added such imperishable lustre.”

The Spencers built their influence by dynastic marriage and through Diana the line will claim its greatest inheritance when her son becomes King.

However, their success is not confined to Britain.

At least half a dozen American presidents have a Spencer ancestry, including George Washington, Franklin D Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge and the two Bush presidents. The common line can be traced back to Henry Spencer, born around 1420. He married Isabella Lincoln and their son William founded the line that would produce Sir Winston Churchill and Diana, Princess of Wales.

The descendants of another son, John Spencer, settled in the New World, and they would be the ancestors of the American presidents. It is claimed – though this is disputed by some genealogists – that if you go back far enough, the common ancestor of the Spencers was a Norman, Robert le Despenser, William the Conqueror’s steward. The Churchills also trace their ancestry to a Norman, Roger de Courcil.

So the common heritage of the greatest Britons turns out to be French, as indeed was that of Isambard Kingdom Brunei, who was second on the list. His father Marc Isambard Brunei, a French naval lieutenant, was a royalist who fled France in 1793. In England he was introduced to some aristocrats who would become his patrons: Earl and Countess Spencer.

Mystery lifted on queen’s powers

The Guardian, Tuesday October 21, 2003

by Clare Dyer

One of the last great riddles of the British political system was solved yesterday when the powers wielded by the government in the name of the monarchy were set down on paper for the first time.

The “veil of mystery” surrounding the royal prerogative was lifted when a list of them was published in a move intended to encourage greater transparency.

The prerogative, which includes the power to declare war, is handed from monarchs to ministers and allows them to take action without the backing of parliament.

In a move intended to encourage greater accountability, the Commons public administration committee (PAC) published a list of the little-understood powers which it persuaded Sir Hayden Phillips, permanent secretary to the Department of Constitutional Affairs, to supply.

“Over the years when people have asked the government to say what prerogative powers there are, they have always refused to do so,” said the committee’s chairman, Labour MP Tony Wright.

“It tells us largely what we know, but it is a small victory to have the government say at least what it thinks they are.”

The PAC wants parliament to be given a say in how the powers are used. Although MPs were given a vote on the war in Iraq, there is no obligation on the government to let them have a say.

The powers include those that allow governments to regulate the civil service, issue passports, make treaties, appoint and remove ministers and grant honours.

They also include the prerogative of mercy, which is no longer used to save condemned men from the scaffold but can be exercised to remedy miscarriages of justice which are not put right by the courts.

In its paper the government said new prerogative powers could not be invented and that some “have fallen out of use altogether, probably forever”, such as the power to press men into the navy. But it said there were still “significant aspects” of domestic affairs in which the powers could be used, despite legislation.

And it accepted that the “conduct of foreign affairs remains very reliant on the exercise of prerogative powers” and that they can “still to some extent adapt to changed circumstances”.

It also set out ways in which parliament and the courts have limited the powers through control of the supply of money, new laws and judicial review.

Mr Wright said: “It should be a basic constitutional principle that ministers would be required to explain to parliament where their powers come from and how they intend to use them.”

The committee is looking at proposals for an act which would force ministers to seek authorisation from parliament before they exercised some of the powers, which were “sometimes in effect powers of life and death”. These include the power to declare war.

The government said it was not possible to give a comprehensive catalogue of prerogative powers. So there was scope for the courts to identify prerogative powers which had little previous recognition.

In a case about whether the home secretary had power to issue baton rounds to a chief constable without the consent of the police authority, the court held that the crown had a prerogative power to keep the peace within the realm.

Lord Justice Nourse commented: “The scarcity of references in the books to the prerogative of keeping the peace within the realm does not disprove that it exists. Rather it may point to an unspoken assumption that it does”.

Becket Abbey is found in Dublin

The Times

by Audrey Magee

IRISH archaeologists believe that they have uncovered the ruins of a church built by Henry II in atonement for the murder of Thomas а Becket.

The discovery was made during development of a derelict site in the centre of Dublin. Archaeologists uncovered walls, decorated window surrounds and painted floor tiles consistent with a 12th-century abbey. The site, near Meath Street, corresponds with a 1610 map showing the site of the Abbey of St Thomas the Martyr.

Daire O’Rourke, an archaeologist with Dublin Corporation, said: “It is a phenomenal find. It is very exciting.” The Corporation and National Monuments Service stopped the development and is to spend Ј250,000 excavating the site. The developer has been given an alternative site in the city.

Henry II commissioned the abbey outside the walls of Dublin in 1177 as part of his penance for the murder in 1170 of Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was canonised in 1173. Becket was murdered in his cathedral by four knights who had reputedly overheard Henry ask if no one would “rid me of this turbulent priest”. The former friends had come into conflict over the relative powers of Church and State.

The abbey built in St Thomas’s memory was a thriving Augustinian foundation and an important religious house for more than 350 years, until Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Excavation is not expected to begin until next year. The site has been recovered with earth to protect it from vandals or art thieves and there are security guards.

Pope had to push reluctant envoy

by Robin Young

Saint Augustine, whose arrival in Kent was commemorated yesterday, was not himself a valiant or resolute pilgrim.

Sent by Pope Gregory the Great at the head of a band of 40 missionary-monks to renew Christianity in a land where it had been largely overrun by barbarous pagan hordes of Jutes, Angles and Saxons, he suffered a bad attack of cold feet en route through Gaul. He returned to Rome to beg the Pope to recall him and his men, explaining that his companions were “appalled at the idea of going to a barbarous, fierce and pagan nation of whose very language they were ignorant.”

The Pope, however, was firm. “My very dear sons,” he responded, “it is better never to undertake any high enterprise than to abandon it once begun. So with the help of God you must carry out this task which you have started.”

In fact, conditions were not quite as dreadful as Augustine had feared. There were already Christians in Britain and an established Christian tradition. St Alban had been martyred in about 209, but a Bishop of London had attended the Council of Arles in 314. In the North, St Columba, the 1,400th anniversary of whose death is also marked this year, had already spread Celtic Christianity from its outpost in Ireland.

Indeed, when Augustine and his 40 monks came ashore at Ebbsfleet, on Pegwell Bay, in 597AD, they were to be welcomed by a Christian Queen, Bertha, a prankish princess who prayed for 35 years that her husband, Ethelbert, should also be converted.

Ethelbert remained a pagan, but he allowed the saint’s monks to rebuild the Roman ruin of St Martin’s Church in Canterbury as a private chapel for his wife, and gave them the land for their abbey and for Canterbury’s first cathedral, which burnt down in 1067.

I lost my heart in Norton Conyers

They wreck marriages, empty bank accounts and make absurd demands. Simon Jenkins on houses to die for.

The Times, Saturday, September 27, 2003

I shall never forget Norton Conyers. The Yorkshire seat of the Grahams has the plain exterior of true antiquity. It is a composition of Dutch gables, Great Hall, ancestral portraits and dusky corridors. In a battered walled garden, promiscuous peonies run wild. Visitors are shown round by Sir James Graham and his wife, who gaze reverentially at their majestic forebears, who gaze doubtfully back at them. Grahams fought at Marston Moor and hunted with the Quorn. Today they tight taxmen and hunt tourists.

This is no stately pile. Norton is a rambling home where I felt I was more likely to be garrotted by a cobweb than fleeced by a corporate hostess. As Lady Graham paced the old rooms she cursed the Victorian baronet, “Number Seven”, for spending so much on “fast women and slow horses” and muttered of her husband that “it is divorce next year if he doesn’t get me a bathroom”. Yet hidden upstairs is Aladdin’s cave, the most atmospheric attic in England, a roofspace thick with unopened steamer trunks, old prints, books and paraphernalia, all joyfully uncatalogued. In a distant gable is a garret where a mad aunt was incarcerated in the 1830s, the original of Mrs Rochester in Jane Eyre. Charlotte Bronte came to Norton as a governess in 1839. The rocking chair and hip bath remain to this day.

Norton Conyers is one of the infantry houses of England. They march in a straggling line behind the squadrons of ducal estates and National Trust properties. Their charm lies as much in their present struggle as in their past. I must confess to having fallen in love with them. They are quite unlike my former obsession of parish churches. A church is a public building erected for one purpose. Most are dark and sombre places, each one like another to the untutored eye. Houses have minds and personalities of their own. They are doors to be unlocked by human interest.

I first visited Eastnor in Herefordshire on a glorious summer day last year. Stone turrets rose over the green lake as if eager to escape across the Malvern Hills. The ancestral owner, James Hervey-Bathurst, had just finished restoring the Regency Picturesque castle that his mother had thought to blow up 50 years earlier. For more than a decade his wife, Sarah, had undertaken one of the boldest and most dramatic refurbishments of a stately home in England. Pugin interiors were brought back to life. Grey walls were softened with fabrics, furniture was chosen in keeping with the pictures. The place was glowing with dark, exciting colours.

Yet no sooner was the work completed than Sarah Hervey-Bathurst left her husband and the gilded vaults of Eastnor to return to her roots in Yorkshire. It was as if the house itself had been the labour of love – as if the Hervey-Bathursts had been married to Eastnor, rather than each other. For all the personal sadness involved, I have to admit that the story of Eastnor’s recent past gives it most colour. Every house needs a story. Otherwise it lies flat on the landscape, a place of two dimensions.

I have found that most historic houses become a mйnage а trois. At modest Detton Hall in Shropshire, Eric Radcliff showed me round the medieval manor which he has spent a lifetime unearthing, salvaging and moulding. In the kitchen his wife was silently making pies. Houses, he confided ominously, “are terrible wife-killers”. The owner of Jacobean Carnfield in Derbyshire emerged from the scaffolding to apologise that both his wife and his builder had just left him, the latter apparently the more serious loss. Small Wonder that at Higham Park in Kent Patricia Gibb and her partner, Amanda Harris-Deans, “amicably separated from their husbands” before teaming up to restore the house in 1995.

The bonds that tie houses to people are the true guardians of these places. Together they constitute the greatest collective treasure trove in Europe. Cathedrals and churches have their place, as do historic towns. But nowhere can equal the splendour of these houses in both architecture and contents. And it is the staying power of the owners that is most astonishing.

Death, revolution and taxes may come and go, but there are Marlboroughs still at Blenheim, Bedfords at Woburn, Buccleuchs at Boughton, Norfolks at Arundel, Exeters at Burghley, Rutlands at Haddon and Salisburys at Hatfield. Nor need we list only the grandees. There have been Berkeleys at Berkeley in Gloucestershire since the Conquest, Benthalls at Benthall in Shropshire and Comptons at Compton in Devon. Descendents of the ancient line of de Vere still preside over Norman Hedingham in Essex.

I have visited well over a thousand houses to make my selection and have come to the conclusion that the English house is God’s gift to eccentricity. The astonishing neo-Jacobean mansion of Harlaxton in Lincolnshire, fantasy palace of the Victorian Gregory Gregory, was rescued by a coal porter’s daughter named Violet Van de Elst. She invented brushless shaving cream and amassed the fortune with which she not only bought the property but communed there with the spirits of the dead at nocturnal seances. She also conducted ceaseless litigation against all who crossed her, alive or dead. The house was finally consigned to the care of University of Indiana.

When Chastieton in Oxfordshire passed to the National Trust in 1991 the owner, Mrs Clutton-Brock, pleaded for the cobwebs to be left in place on the plausible grounds that they were all that held the building together. Her family had always attributed their poverty to losing everything in the war – “the Civil War, of course”. Indeed, such old ladies are pure gold. Visiting Kentwell in Suffolk some 20 years ago I was mesmerised to see an old lady roped off in an armchair quietly watching the racing on television. The household granny had apparently refused to budge, despite being told that the public was arriving. People thought her a waxwork.

Sometimes it became even harder to tell reality from invention. At Belmont in Cheshire, a minor gem by James Gibbs, “A Pair of Cher’s knickers” hangs in a glass case over the drawing-room fireplace. Nobody could tell me why. At Clarke Hall in Wakefield I noticed that the chamber pots were empty. At Dennis Severs’s bizarre house in Spitalfields they were alarmingly full.

Such houses often play host to history. At ancient Hemmingford Grey in Huntingdonshire a trumpet gramophone still sits in the hall upstairs, awaiting the return of the young American pilots who came for tea dances during the war. At Deene Park in Northamptonshire, Lord Cardigan’s mummified horse, which brought him back safe from the Charge of the Light Brigade, has rotted away to just its head. At Charleston in Sussex, the country retreat of the Bloomsbury set, a “family tree” indicates the sexual as well as familial relations between the occupants. Holdsworth House in Yorkshire, now a hotel, carries the mind-boggling boast that “Jayne Mansfield and Alec Douglas-Home slept here”. At Freud’s House in Hampstead the objects are labelled not with names but with suitable dreams.

Buried improbably in suburban Paignton, outside Torquay, I encountered the extraordinary creation of young Paris Singer, heir to Isaac Singer’s sewing machine fortune. In 1904 he decided to build a cross between Versailles and the Place de la Concorde, complete with Louis XIV’s Hall of Mirrors. Craftsmen were despatched to Paris for precise measurements. The great staircase was hung with David’s Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine, for which Singer outbid the Louvre. When the painting was finally sold to France after the last war, an armoured train was sent to collect it. The house stands to this day, occupied by the town council. While the mayor lives in Napoleonic splendour, local people can marry in the Hall of Mirrors.

The struggle to keep these places upright can be titanic. In the two hours I spent with Sir Humphrey Wakefield at Chillingham Castle, he did not draw breath in describing his fight to restore the mighty Northumberland seat of the Greys. Enemies were once Scots marauders. Now they are taxmen, English Heritage and health and safety inspectors “in jackboots”. Farther south, on a bleak hill overlooking Burton-on-Trent, Kate Newton is battling against wind and rain to prop up collapsing Sinai House, living in one half of this medieval remain while the other is draped in dangerous-structure notices. She deserves a medal.

The fact is that for every Lord Spencer of Althorp, whose jewelled wedding shoes were valued at Ј30,000 in the mid-18th century, there was a Verney, a Cobham or a Walpole reduced to poverty by architectural ambition. Wimpole Hall outside Cambridge is said to have ruined every owner for three hundred years. In 1845 the bankrupt Duke of Buckingham entertained Victoria and Albert at his family seat of Stowe, while the bailiffs waited behind bushes outside to pounce as soon as the monarch had departed. Architects have done more to undermine the English aristocracy than wars or death duties.

Of my thousand houses roughly half are now in the public sector, divided between the National Trust, English Heritage and local councils. For all the criticism visited on these bodies and their often bloodless house style, they stopped the appalling demolitions in the decades after the Second World War. The National Trust was Britain’s finest “nationalisation”. It rescued not just buildings such as Knole, Hardwick and Kedleston but lesser pleasures such as Tintagel Post Office and the delightful farm of Townend in Cumbria.

I have embraced in my list as many types and styles of house as possible. Smaller ones often depend on an association with a famous occupant, such as the four houses attributed to Dickens in London and Kent. Kipling’s home at Bateman’s in Sussex still reeks of Kim, India and pipe tobacco. Nobody can visit Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top in the Lake District and miss the ghosts of Tom Kitten, Pigling Bland and Jemima Puddleduck. As for Lawrence of Arabia’s Dorset cottage, it may be devoid of architectural distinction, but it sits in its wood as if waiting for that strange, secretive man to return from the fatal motorcycle ride over the hill outside. Such shrines are surely still inhabited.

Anywhere that men and women have laid their heads is, to me, a house. I visited England’s grimmest jail, at Walsingham in Norfolk, and most charming almshouse, in Cobham in Kent. Hotel use has saved many buildings from demolition. Langley in Northumberland offers a chance to stay in a medieval pele tower in the woods. Off the Devon coast is Art Deco Burgh Island, built by an infatuated tycoon for his starlet wife. Now a hotel, it beams out over the bay where a jazz band once played on a raft for swimming parties.

Most moving of all is Kingston Lacy. This magnificent house was created by the Regency rake William Bankes, after a youth so dissipated that even Byron described him as “my father of mischief”. Forced by his homosexuality to flee the country, Bankes built and filled his new house entirely by letter from Venice, sending packing cases crammed with pictures and furniture. Pledged never to return on pain of imprisonment, he paid his debt to his family’s past and future with this monument in his home estate.

Many years later, when Bankes was forgotten in exile, it is said that a dark, cloaked figure arrived by coach one night at the Kingston gatehouse. The custodian unlocked the big house and torchlight illuminated each fine room in turn. The figure then vanished into the night. Bankes, we hope, was proud of his life’s work.

The houses of England – palaces, mansions, terraces and huts – are its most precious relic because they are its most intimate creation. Most have been threatened and many have been lost, but an astonishing array survives. To visit them is still the nearest we get to shaking hands with history.