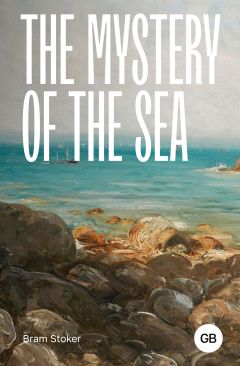

Текст книги "The Mystery of the Sea / Тайна моря"

Автор книги: Брэм Стокер

Жанр: Исторические приключения, Приключения

Возрастные ограничения: +16

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

That the original cipher, as given, can be so reduced is ma-nifest. Of the Quintuple biliteral there are thirty-two combinations. As in the Elizabethan alphabet, as Bacon himself points out, there were but twenty-four letters, certain possibilities of reduction at once unfold themselves, since at the very outset one entire fourth of the symbols are unused.

Appendix B

On the Reduction of the Number of Symbols In Bacon's Biliteral Cipher

When I examined the scripts together, both that of the numbers and those of the dots, I found distinct repetitions of groups of symbols; but no combinations sufficiently recurrent to allow me to deal with them as entities. In the number cipher the class of repetitions seemed more marked. This may have been, however, that as the symbols were simpler and of a kind with which I was more familiar, the traces or surmises were easier to follow. It gave me hope to find that there was something in common between the two methods. It might be, indeed, that both writings were but variants of the same system. Unconsciously I gave my attention to the simpler form-the numbers-and for a long weary time went over them forward, backward, up and down, adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing; but without any favorable result. The only encouragement which I got was that I got additions of eight and nine, each of these many times repeated. Try how I would, however, I could not scheme out of them any coherent result.

When in desperation I returned to the dotted papers I found that this method was still more exasperating, for on a close study of them I could not fail to see that there was a cipher manifest; though what it was, or how it could be read, seemed impossible to me. Most of the letters had marks in or about them; indeed there were very few which had not. Examining more closely still I found that the dots were disposed in three different ways: (a) in the body of the letter itself: (b) above the letter: (c) below it. There was never more than one mark in the body of the letter; but those above or below were sometimes single and sometimes double. Some letters had only the dot in the body; and others, whether marked on the body or not, had no dots either above or below. Thus there was every form and circumstance of marking within these three categories. The only thing which my instinct seemed to impress upon me continually was that very few of the letters had marks both above and below. In such cases two were above and one below, or vice versa; but in no case were there marks in the body and above and below also. At last I came to the conclusion that I had better, for the time, abandon attempting to decipher; and try to construct a cipher on the lines of Bacon's Biliteral-one which would ultimately accord in some way with the external conditions of either, or both, of those before me.

But Bacon's Biliteral as set forth in the Novum Organum had five symbols in every case. As there were here no repetitions of five, I set myself to the task of reducing Bacon's system to a lower number of symbols-a task which in my original memorandum I had held capable of accomplishment.

For hours I tried various means of reduction, each time getting a little nearer to the ultimate simplicity; till at last I felt that I had mastered the principle.

Take the Baconian biliteral cipher as he himself gives it and knock out repetitions of four or five aaaaa: aaaab: abbbb: baaaa: bbbba: and bbbbb. This would leave a complete alphabet with two extra symbols for use as stops, repeats, capitals, etc. This method of deletion, however, would not allow of the reduction of the number of symbols used; there would still be required five for each letter to be infolded. We have therefore to try another process of reduction, that affecting the variety of symbols without reference to the number of times, up to five, which each one is repeated.

Take therefore the Baconian Biliteral and place opposite to each item the number of symbols required. The first, (aaaaa) requires but one symbol “a,” the second, (aaaab) two, “a” and “b;” the third (aaaba) three, “a” “b” and “a;” and so on. We shall thus find that the 11th (ababa) and the 22nd (babab) require five each, and that the 6th, 10th, 12th, 14th, 19th, 21st, 23rd and 27th require four each. If, therefore, we delete all these biliteral combinations which require four or five symbols each-ten in all-we have still left twenty-two combinations, necessitating at most not more than two changes of symbol in addition to the initial letter of each, requiring up to five quantities of the same symbol. Fit these to the alphabet; and the scheme of cipher is complete.

If, therefore, we can devise any means of expressing, in conjunction with each symbol, a certain number of repeats up to five; and if we can, for practical purposes, reduce our alphabet to twenty-two letters, we can at once reduce the biliteral cipher to three instead of five symbols.

The latter is easy enough, for certain letters are so infrequently used that they may well be grouped in twos. Take “X” and “Z” for instance. In modern printing in English where the letter “e” is employed seventy times, “x” is only used three times, and “z” twice. Again, “k” is only used six times, and “q” only three times. Therefore we may very well group together “k” and “q,” and “x” and “z.” The lessening of the Elizabethan alphabet thus effected would leave but twenty-two letters, the same number as the combinations of the biliteral remaining after the elision. And further, as “W” is but “V” repeated, we could keep a special symbol to represent the repetition of this or any other letter, whether the same be in the body of a word, or if it be the last of one word and the first of that which follows. Thus we give a greater elasticity to the cipher and so minimise the chance of discovery.

As to the expression of numerical values applied to each of the symbols “a” and “b” of the biliteral cipher as above modified, such is simplicity itself in a number cipher. As there are two symbols to be represented and five values to each-four in addition to the initial-take the numerals, one to ten-which latter, of course, could be represented by 0. Let the odd numbers according to their values stand for “a”:

a=1

aa=3

aaa=5

aaaa=7

aaaaa=9

and the even numbers according to their values stand for “b”:

b=2

bb=4

bbb=6

bbbb=8

bbbbb=0

and then? Eureka! We have a Biliteral Cipher in which each letter is represented by one, two, or three, numbers; and so the five symbols of the Baconian Biliteral is reduced to three at maximum.

Variants of this scheme can of course, with a little ingenuity, be easily reconstructed.

Appendix C

The Resolving of Bacon's Biliteral Reduced to Three Symbols in a Number Cipher

Place in their relative order as appearing in the original arrangement the selected symbols of the Biliteral:

a a a a a

a a a a b

&c

Then place opposite each the number arrived at by the application of odd and even figures to represent the numerical values of the symbols “a” and “b.”

Thus aaaaa will be as shown 9

aaaab will be as shown 72

aaaba will be as shown 521

and so on. Then put in sequence of numerical value. We shall then have: 0. 9. 18. 27. 36. 45. 54. 63. 72. 81. 125. 143. 161. 216. 234. 252. 323. 341. 414. 432. 521. 612. An analysis shows that of these there are two of one figure; eight of two figures; and twelve of three figures. Now as regards the latter series-the symbols composed of three figures-we will find that if we add together the component figures of each of those which begins and ends with an even number they will tot up to nine; but that the total of each of those commencing and ending with an odd number only total up to eight. There are no two of these symbols which clash with one another so as to cause confusion.

To fit the alphabet to this cipher the simplest plan is to reserve one symbol (the first-“0”) to represent the repetition of a foregoing letter. This would not only enlarge possibilities of writing, but would help to baffle inquiry. There is a distinct purpose in choosing “0” as the symbol of repetition for it can best be spared; it would invite curiosity to begin a number cipher with “0,” were it in use in any combination of figures representing a letter.

Keep all the other numbers and combinations of numbers for purely alphabetical use. Then take the next five-9 to 45 to represent the vowels. The rest of the alphabet can follow in regular sequence, using up of the triple combinations, first those beginning and ending with even numbers and which tot up to nine, and when these have been exhausted, the others, those beginning and ending with odd numbers and which tot up to eight, in their own sequence.

If this plan be adopted, any letter of a word can be translated into numbers which are easily distinguishable, and whose sequence can be seemingly altered, so as to baffle inquisitive eyes, by the addition of any other numbers placed anywhere throughout the cipher. All of these added numbers can easily be discovered and eliminated by the scribe who undertakes the work of decipheration, by means of the additions of odd or even numbers, or by reference to his key. The whole cipher is so rationally exact that any one who knows the principle can make a key in a few minutes.

As I had gone on with my work I was much cheered by certain resemblances or coincidences which presented themselves, linking my new construction with the existing cipher. When I hit upon the values of additions of eight and nine as the component elements of some of the symbols, I felt sure that I was now on the right track. At the completion of my work I was exultant for I felt satisfied in believing that the game was now in my own hands.

Appendix D

On the Application of the Number Cipher to the Dotted Printing

The problem which I now put before myself was to make dots in a printed book in which I could repeat accurately and simply the setting forth of the biliteral cipher. I had, of course, a clue or guiding principle in the combinations of numbers with the symbols of “a” and “b” as representing the Alphabetical symbols. Thus it was easy to arrange that “a” should be represented by a letter untouched and “b” by one with a mark. This mark might be made at any point of the letter. Here I referred to the cipher itself and found that though some letters were marked with a dot in the centre or body of the letter, those both above and below wherever they occurred showed some kind of organised use. “Why not,” said I to myself, “use the body for the difference between “a” and “b;” and the top and bottom for numbers?”

No sooner said than done. I began at once to devise various ways of representing numbers by marks or dots at top and bottom. Finally I fixed, as being the most simple, on the following:

Only four numbers-2, 3, 4, 5-are required to make the number of times each letter of the symbol is repeated, there being in the original Baconian cipher, after the elimination of the ten variations already made, only three changes of symbol to represent any letter. Marks at the top might therefore represent the even numbers “2” and “4”-one mark standing for “two” and two marks for “four”; marks at the bottom would represent the odd numbers “3” and “5”-one mark standing for “three” and two marks for “five.”

Thus “a a a a a” would be represented by “a¨” or any other letter with two dots below: “a a a a b” by ä b, or any other letters similarly treated. As any letter left plain would represent “a” and any letter dotted in the body would represent “b” the cipher is complete for application to any printed or written matter. As in the number cipher, the repetition of a letter could be represented by a symbol which in this variant would be the same as the symbol for ten or “0.” It would be any letter with one dot in the body and two under it, thus – t¨.

For the purpose of adding to the difficulty of discovery, where two marks were given either above or below the letter, the body mark (representing the letter as “b” in the Biliteral) might be placed at the opposite end. This would create no confusion in the mind of an advised decipherer, but would puzzle the curious.

On the above basis I completed my key and set to my work of deciphering with a jubilant heart; for I felt that so soon as I should have adjusted any variations between the systems of the old writer and my own, work only was required to ultimately master the secret.

The following tables will illustrate the making and working-both in ciphering and de-ciphering-of the amended Biliteral Cipher of Francis Bacon:

CIPHER FOR NUMBERS AND DOTS

P (Plain) means letter left untouched ↔ D (Dot) means letter with dot in body

One Dot – (.) at Top (t) = 2 ↔ One Dot – (.) at Bottom (b) =3

Two Dots – (…) at Top (t) = 4 ↔ Two Dots – (…) at Bottom (b) = 5

Note.-When there are to be two dots at either top or bottom of a letter, the dot usually put in the body of a letter which is to indicate “b” can be placed at the opposite end of the letter to the double dotting. This will help to baffle investigation without puzzling the skilled interpreter.

KEY TO NUMBER CIPHER

Divide off into additions of nine or eight. Thus if extraneous figures have been inserted, they can be detected and deleted.

Cipher.

A=9

B = 54

C = 63

D = 72

E = 18

F = 81

G = 216

H = 234

I = 27

K.Q = 252

L = 414

M = 432

N = 612

O = 36

P = 125

R = 143

S = 161

T = 323

U.V = 45

X.Z = 341

Y = 521

Repeat = O

De-Cipher.

O=Repeat Letter

125 = P

143 = R

161 = S

18 = E

216 = G

234 = H

252 = K or Q

27 = I

323 = T

341 = X or Z

36 = O

414 = L

432 = M

45 = U or V

521 = Y

54 = B

612 = N

63 = C

72 = D

81 = F

9 = A

FINGER CIPHER

Values the same as Number Cipher.

The RIGHT hand, beginning at the thumb, represent the ODD numbers,

The LEFT hand, beginning at the thumb, represent the EVEN numbers.

KEY TO DOT CIPHER

MEMORANDA

Begin fresh with each line.

Take no account of stops.

Take no account of Capitals or odd words.

ye is one letter.

Appendix E

Page —

Narrative of Bernardino de Escoban, Knight of the Cross of the Holy See and Grandee of Spain

When my kinsman who was known as the “Spanish Cardinal” heard of my arrival in Rome in obedience to his secret summons, he sent one to me who took me to see him at the Vatican. I went at once and found that though the carriage of his great office had somewhat aged my kinsman it had not changed the sweet bearing which he had ever had towards me. He entered at once on the matter regarding which he had summoned me, leaving to later those matters of home and family which were close to us both, and prefacing his speech with an assurance-unnecessary I enforced on him-that he would not have urged me to so great a voyage, and at a time when the concerns of home and of His Catholic Majesty so needed me in my own place, had there not been strictest need of my presence at Rome. This he then explained, ever anticipating my ignorance, so lucidly and with sweet observance of my needs, that I could not wonder at his great advancement.

Entering at once on the enterprise of the King as to the restoration of England to the fold of the True Church he made clear to me that the one great wish of His Holinesse was to aid in all ways the achievement of the same. To such end he was willing to devote a vast treasure, the which he had accumulated for the purpose through many years. “But” said my kinsman, and with so much smiling as might become his grave office “the King hath here at the Court of Rome one to represent him, who, though doubtless a zealous and faithful servant of his Royal Master, hath not those qualities of discretion and discernment, of the subjugation of self and the discipline of his own ideas, which go to make up the perfection of the Ambassador. He hath already many times and in many ways, to many persons and in many Countries, said of His Holinesse such things as, even if true-and they are not so-were, in the high discretion of his office as Ambassador, better unspoken. This, moreover, in an Embassy wherein he wishes to acquire much which the mundane world holds to be of great worth. The Count de Olivares hath spoken freely and without reserve of the Holy Father's reticence in handing over vast sums of money to His Catholic Majesty as due to parsimony, to avarice, to meanness of spirit, and to other low qualities which, though common enough in men, are soil to the name of God's Vicegerent on Earth! Nay” he went on, seeing that my horror was such as to verge on doubt, “trust me in this, for of the verity of these things I am assured. Rome hath many eyes, and the hearing of her ears is widecast. The Pope and his Cardinals are well served throughout the world. Little indeed happens in Christendom-aye and beyond it-which is not echoed in secret in the Vatican. I know that not only has Count de Olivares spoken of his beliefs regarding the Holy Father to his mundane friends, but he has not hesitated in his formal despatches to say the same to his Royal Master. It hath grieved His Holinesse much that any could so misunderstand him, and it hath grieved him more that His Catholic Majesty should receive such calumnies without demur. Wherefore he would take some other means than the hand of the King of Spain to accomplish his own secret ends. He knoweth well the high purpose of His Catholic Majesty, your Royal Master, in the restoration of England to the True Faith; but yet his mind is much disturbed by his recent pronouncements regarding the Bishoprics. The See of Rome is the Arch Episcopate of the Earth, and to its Bishop belongs by God's very ordinance the ruling of all the bishoprics of the Church. “Upon this Rock shall I build my Church.” Now His Holinesse hath already promised a million crowns towards the great emprise of the Armada; and he hath promised it so that it be handed over to the King when his emprise, which is after all for the enlargement of his own kingdom, hath begun to bear fruit. But Count de Olivares is not content with this promise-the promise remember of God's Vicegerent-and he is ever clamorous, not only for the immediate payment of this promised sum, but for other sums. His new request is for another million crowns. And even in the very presence of His Holinesse, he so bears himself as if the non-compliance with his demand were a wrong to him and to his Master. From all which His Holinesse, consulting in privacy with me who am also his friend-such is the greatness with which he honoureth me-hath determined that, whereas he will of course keep to the last letter his promise of help, and will even exceed largely the same, he will dispose in other ways of the great treasure which he had already set aside for this English affair. When he honoured me by asking my advice as to whom should be entrusted with this high endeavour, and had shown that of necessity it should be some Spaniard so that hereafter it might not be said that the emprise of the Armada had not his full sanction and support, I ventured to suggest that in you first of all men this high trust should be reposed. For yourself, I said that I had known you from childhood, and had found you without a flaw; and that you came from a race that had gone clothed in honour since the time of the Moors.”

Much other of like kind, my children, did my kinsman tell me that he had said to His Holinesse; which so satisfied him that he had commanded him to send for me so that he could have the assurance of his own seeing what manner of man I was. My kinsman then went on to tell me how he had told His Holinesse of what I had already taken in hand regarding the Great Armada. How I had promised the King a galleon fully equipped and manned with seamen and soldiers from our old Castile; and how His Majesty was so pleased, since my offer had been the first he had received, that he had sworn that my vessel should carry the flag of the squadron of the galleons of Castile. He told him also that the galleon was to be called the San Cristobal from my patron saint; and also that so her figurehead should bear the image of the Christ into English waters the first of all things that came from my Province. Which idea so wrought upon the mind of His Holinesse that he said: “Good man! Good Spaniard! Good Christian! I shall provide the figurehead for the San Cristobal myself. When Don de Escoban comes here I shall arrange it with him.”

When my kinsman had so informed me as to many things he left me a while, saying that he would ask the Pope to arrange for an audience with me. Shortly he returned with haste, saying that the Holy Father wished me to come to him at once. I went in exaltation mingled with fear; and all my unworthiness of such high honour rose before me. But when I came to His Holinesse and knelt before him he blessed me and raised me up himself. And when he bade me, I raised my eyes and looked at him in the face. Whereat he turned to the Spanish Cardinal and said: “You have spoken under the mark, my brother. Here is a man indeed in whom I can trust to the full.”

And so, my children, he made me sit by him, and for a long time-it was more than two hours by the clock-he talked with me about his wish. And, oh my children, I would that you and others could hear the wise words of that great and good man. He was so worldly-wise, in addition to his Saintly wisdom, that nothing seemed to lack in his reasoning; nothing was too small to be outside his understanding and considerations of the motives and arts of men. He told me with exceeding frankness of his views of the situation. All the while, my kinsman smiled and nodded approval now and again; and it filled me with pride that one of my own blood should stand so close to the counsels of His Holinesse. He told me that though war was a sad necessity, which he as himself an earthly monarch was compelled to understand and accept, yet he preferred infinitely the ways of peace; and moreover believed in them. In his own wise words, “the logic of the cannon, though more loud, speaks not so for-cibly as the logic of the living day between sunrise and sunset.” When later he added to this conviction that, “the chink of the money-bag speaks more loudly than either,” I ventured an impulsive word of protest. Whereupon he stopped and looking at me sharply asked if I knew how to bribe. To which I replied that as yet I had given none, nor taken none. Then smilingly he laid his hand in friendlinesse on my shoulder and said: “My friend, Saint Escoban, these be two things, not one; and though to take a bribe is to be unforgiven, yet to give one at high command is but a duty, like the soldier's duty to kill which is not murder, which it would be without such behest.” Then raising his hand to silence my protest he said: “I know what you would say: 'Woe to that man by whom the scandal cometh,' but such argument, my friend, is my province; and its responsibility is mine. Ere you proceed on your mission you shall have indemnity for the carriage of all my commands. You go into an enemy's country; a country which is the professed and malignant enemy of Holy Church, and where faith and honour are not. God's work is to be done in many ways. It is sufficient that He has allowed instruments that are unworthy and unholy; and as unworthy and unholy we must use them to His ends. You, Don de Escoban, shall have no pain in such matters, and no shame. My commands shall cover you!” Then, when I had bowed my recognition of his will, he resumed his instructions. He said that in England in high places were many men who were open to sell their knowledge or their power, and that when once they had accepted payment it were needful for their own credit and even for their safety, that they should further the end which they had undertaken. “These English,” he said, “are pagans; and it was said of this our Holy City in pagan times 'Omnia Romae venalia sunt!'” Whereupon there was borne upon me a recollection of years before when I was in the suite of the Ambassador at Paris, how a boy in the British Embassy who was shewing me a cipher of encloased writing which he had just perfected had written in it with uncouth lettering as an illustration “Omnia Britaniae venalia sunt.” And further did remember how we had enlarged and perfected the cipher when we resided together at Tours. His Holinesse told me that in great seasons it were needful to scatter favours with a lavish hand, and that no season was or could be so great as that which foreran the restoring to the fold a great and active nation who was already beginning to rule the seas. “To which end,” he said, “I am placing with you a vastness of treasure such as no nation hath ever seen. The gifts of the Faithful have begun it and enlarged it; and the fruits of many victories have enhanced it. Regarding it, there is only one promise which I will exact from you, and that I shall exact in the most solemn way of which the Church has knowledge; that this vast treasure be applied to onely that purpose to which it is ordained-the advancement of the True Faith. It will add also, of course, to the honour and glory of the Kingdom of Spain, so that for all time the world may know that the comfort of the Roman See is on the emprise of the Great Armada! In proof of which should, for the sins of men, the great emprise fail, you or those who may succeed you in the Trust are, if I myself be not then living, to hand the Treasure to the custody of whatever monarch may then sit upon the throne of Spain for his good guardianship, in trust with me.”

So he proceeded to detail; and gave full instructions as to the amount of the treasure. How it was to be placed in my hands, and when; and all details of its using when the Armada should have made landing on English shores. And how I should use it myself, in case I were not told to hand it over to some other. If I were to yield up the treasure, the mandate should be enforced by letter, together with the showing of a ring, which he took from the purse where he kept the Fisherman's ring wherewith he signs all briefs, and allowed me to examine it so that I might recognize it if shown to me hereafter. All of which things of using are not now of importance to you, my children, for the time of their usefulness has passed by; but only to show that the treasure is to be guarded, and finally given to the custody of the King of Spain.

Then His Holiness spoke to me of my own vessel. He pro-mised me that a suitable figurehead, one wrought for his own galley by the great Benvenuto Cellini, and blessed by Himself, should be duly sent on to me. He promised also that the Quittance to me and mine, which he had named should be completed and lodged in the secret archives of the Papacy. Then once more he blessed me, and on parting gave me a relic of San Cristobal, whose possession, together with the honour done me, made me feel as I left the Vatican as though I walked upon air.

On my return to Spain I visited the ship yard at San Lucar, where already the building of the San Cristobal was in progress. I arranged in private with the master builder that there should be constructed in the centre of the galleon a secret chamber, well encased round with teak wood from the Indies, and with enforcement of steel plates; and with a lock to the iron door, such as Pedro the Venetian hath already constructed for the treasure chest of the King. By my suggestion, and his wisdom in the doing of the matter, the secret chamber was so arranged in disposition, and so masked in with garniture of seeming unimportance, that none, unless of the informed, might tell its presence, or indeed of its very existence. It was placed as though in a well of teak wood and steel, hemmed in on all sides; without entrance whatever from the lower parts, and only approachable from the top which lay under my own cabin, down deep in the centre of the galleon. Men in single and detachments, were brought from other ship yards for the doing of this work, and all so disposed in Port that none might have greater knowledge than of that item which he completed at the time. Save only those few of the guilds whose faith had long been made manifest by their rectitude of life and their discretion of silence.

Into this secret receptacle (to continue this narrative out of its due sequence) when the final outfitting of the Invincible Armada came to pass, was placed, under my own supervision, in the night time and in secret, all the vast treasure which had before then been sent to me secretly by agents of His Holinesse. Full tally and reckoning made I with my own hand, nominating the coined money by its value in crowns and doubloons, and the gold and silver in bullion by their weight. I made a list in separate also of the endless array of precious stones, both those enriched in carvings and inriching the jewells of gold and silver wrought by the cunning of the great artizans. I made list also of the gems unplanted, which were of innumerable number and of various bigness. These latter I specified by kind and number, singling out some of rare size and quality for description. The whole table of the list I signed and sent by his messengers to the Pope, specifying thereon that I had them in trust for His Holinesse to dispose of them as he might direct; or to yield over to whomsoever he might depute to receive them whenever and wherever they might be in the guardianship of me or mine, the order of His Holinesse being verified by the exhibition by the new trustee of the Eagle Ring.

Before the San Cristobal had left San Lucar, there arrived from Rome, in a package of great bulk-brought by a ship accredited by the Pope, so that corsairs other than Turks and pagans might respect the flag, and so abstain from plunder-the figurehead of the galleon which His Holinesse had promised to supply. With it came a sealed missive cautioning me that I should open the package in privacy, and deal with its contents only by means of those in whom I had full trust, since it was even in its substance most precious. In addition to which it had been specially wrought by Benvenuto Cellini, the Master goldsmith whose work was contended for by the Kings of the earth. It was the wish of His Holinesse himself that on the conversion of England being completed, either through peace or war, this figurehead of the San Cristobal should be set over the High Altar of the Cathedral at Westminster, where it would serve for all time of an emblem of the love of the Pope for the wellbeing of the souls of his English children.

Правообладателям!

Это произведение, предположительно, находится в статусе 'public domain'. Если это не так и размещение материала нарушает чьи-либо права, то сообщите нам об этом.