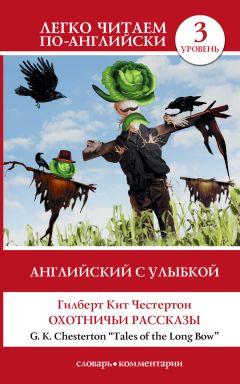

Автор книги: Гилберт Честертон

Жанр: Иностранные языки, Наука и Образование

Возрастные ограничения: +16

сообщить о неприемлемом содержимом

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 5 страниц) [доступный отрывок для чтения: 1 страниц]

Гилберт Кит Честертон

Английский с улыбкой:Охотничьи рассказы = Tales of the Long Bow

© Пирогов М. С., адаптация текста, комментарии, словарь, 2016

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2016

Chapter I. The unpresentable appearance of colonel crane

These stories tell about things recognized as impossible to do. If the writer just said that they happened, without saying how they happened, nobody would believe him, just like no one believes the story about the cow who jumped over the moon.

The first story begins on a straight road of bright houses in a suburb of a big city. The time was about twenty minutes to eleven on Sunday morning, when a procession of suburban families in Sunday clothes were going up the road to church. And the man was a very respectable retired military man named Colonel Crane, who was also going to church, as he had done every Sunday at the same hour for many years. He was dressed very elegantly for church as if for parade; but his clothes did not stand out in any way. He was quite handsome in a dry, sun-baked style; but his blond hair was of a colourless sort, and though his blue eyes were clear, they looked out a little heavily under lowered eyelids.

Colonel Crane belonged to the previous age in the history of England. He was not really old, indeed he was hardly middle-aged, and had received his last medals for the Great War[1]1

Great War – «Великая война», речь идёт о Первой мировой войне (1914–1918).

[Закрыть]. But for a number of reasons he still belonged to the traditional type of the old professional soldiers, the way it had existed before 1914. Each church in those times had only one colonel as it had only one priest. It would be quite unjust to call him an old ruin; indeed, it would be much better to call him a bastion. Because he had remained in the traditions as firmly and patiently as he had stood under enemy fire. He was simply a man who had no taste for changing his habits, and had never worried about conventions enough to change them. One of his excellent habits was to go to church at eleven o’clock, so he went there every Sunday. And he did not know that there went with him something from an old-world atmosphere and a paragraph in the history of England.

When he came out of his front door on that particular morning, he was twisting a piece of paper in his fingers and frowning. Instead of walking straight to his garden gate he walked once or twice up and down his front garden, swinging his black walking-stick. The note had been given to him at breakfast, and it clearly described some practical problem which he needed to solve immediately. He stood for a few minutes looking at a red flower on of the nearest flower-bed; and then a new expression came to his bronzed face. Folding up the paper and putting it into his pocket, he walked round the house to the back garden. Behind the back garden there was a kitchen-garden, in which an old servant named Archer was working as a gardener.

Archer was also a bastion. Indeed, the two had stood together through a number of things that had killed many other good people. But though they had gone through the war together and had a complete confidence in each other, Archer could never lose the manners of a servant. He performed the duties of a gardener as if he were a butler. He really performed the duties very well and enjoyed them very much. Perhaps he enjoyed them so much because he was a clever Cockney[2]2

Cockney – кокни, житель бедных районов Восточного Лондона.

[Закрыть], and for him the country crafts were a new hobby. But somehow, whenever he said, “I have put in the seeds, sir,” it always sounded like, “I have put the drinks on the table, sir”; and he could not say “Should I pull out the carrots?” without seeming to say, “Would you like some red wine?”

“I hope you’re not working on Sunday,” said the Colonel, with a much more pleasant smile than most people got from him, though he was always polite to everybody. “You’re getting too fond of this agricultural hobby. You’ve become an uncultured peasant.”

“I was preparing to examine the cabbages, sir,” replied the uncultured peasant, in a very polite intonation. “Their condition yesterday evening did not look satisfactory to me.”

“Glad you didn’t spend the whole night near them,” answered the Colonel. “But it’s lucky you’re interested in cabbages. I want to talk to you about cabbages.”

“About cabbages, sir?” asked the other respectfully.

But the Colonel did not answer this question. He was suddenly looking in an abstracted way at another object in the vegetable plots in front of him.

We will never understand how a man’s soul and social type always affect his surroundings. Anyhow, the soul of Mr. Archer affected the kitchen-garden. It made his kitchen-garden different from any other. Mr. Archer was after all a practical man, and he liked his new profession much more than we would think.

So the kitchen-garden did not look like somebody’s backyard, it really looked like a corner of a farm in the country. All sorts of practical devices were used there to protect the vegetables and berries from birds. Strawberries were covered with nets, strings with feathers were stretched across the plots, and in the middle of the biggest plot stood an old and authentic scarecrow. Perhaps the only one who could compete with the scarecrow for the crown of the kitchen-garden was the shapeless South Sea idol, which marked the border of the garden’s territory. Colonel Crane would not have been such a typical officer of the old army, if he had not hidden somewhere a hobby connected with his travels. His hobby was folklore of the Oceanic islands and he had a souvenir from there in his garden. At the moment, however, he was not looking at the idol. He was looking at the scarecrow.

“By the way, Archer,” he said, “don’t you think the scarecrow needs a new hat?”

“I think it is hardly necessary, sir,” said the gardener gravely.

“But look here,” said the Colonel, “you should consider the philosophy of scarecrows. In theory, that thing is supposed to convince some rather simple-minded bird that I am walking in my garden. That thing with a terrible hat is me. Perhaps, it is a little bit sketchy. Some sort of impressionist portrait. But it is hardly likely to impress. A man with a hat like that would never be really firm with a sparrow. Conflict of wills, and all that, and I bet the sparrow would be the winner. By the way, what’s that stick tied on to it?”

“I believe, sir,” said Archer, “that it is supposed to represent a gun.”

“It is holding it wrong,” remarked Crane. “A man with a hat like that would miss for sure.”

“Do you want me to buy another hat?” asked the patient Archer.

“No, no,” answered his master carelessly. “Since the poor fellow has such a rotten hat, I’ll give him mine. Like the scene of St. Martin and the beggar[3]3

St. Martin – Св. Мартин, согласно преданию, разрезал свой тёплый плащ пополам, чтобы бедняку было во что завернуться зимой.

[Закрыть].”

“Give him yours,” repeated Archer respectfully, but very quietly.

The Colonel took off his polished top-hat and gravely placed it on the head of the Oceanic idol at his feet. It had a strange effect of making the grotesque piece of stone look alive, as if a goblin in a top-hat was grinning at the garden.

“Do you think the hat shouldn’t be quite new?” he asked almost anxiously. “Not usual among the best scarecrows, perhaps. Well, let’s see what we can do to make it a little older.”

He raised his walking-stick above his head and hit the silk hat with a loud smack, smashing it over the empty eyes of the idol.

“Softened with the touch of time now, I think,” he remarked, holding out what remained of the silken hat to the gardener. “Put it on the scarecrow, my friend; I don’t want it. You can be a witness that it’s no use to me.”

Archer obeyed like a robot. A robot with rather round eyes.

“We must hurry up,” said the Colonel cheerfully. “I was early for church, but I’m afraid I’m a bit late now.”

“Did you plan to attend church without a hat, sir?” asked the other.

“Certainly not. Most disrespectful,” said the Colonel. “Nobody should neglect to remove his hat when he enters church. Well, if I don’t have a hat, I will neglect to remove it. Where is your logic this morning? No, no, just dig up one of your cabbages.”

Once more the well-trained servant managed to repeat the word “Cabbages” with his own polite intonation; but he couldn’t say it very loudly at the moment.

“Yes, go and pull up a cabbage, please,” said the Colonel. “I must really be going; I believe I heard the clock strike eleven.”

Mr. Archer moved heavily in the direction of a plot of cabbages, where many monstrous contours and many colours were open to the eye; objects, perhaps, more worthy of the philosophic eye than is usually taken into account. Vegetables are curious-looking things and less trivial than they sound. If we called a cabbage a cactus, or some other exotic name, we might see it as an equally exotic thing.

The Colonel revealed these philosophical truths by dragging a great, green cabbage with its long root out of the earth, before the dubious Archer had time to do it. He then picked up a knife and cut short the long tail of the root. After that he cut out the inside leaves to create some empty space, and gravely reversing it, placed it on his head. Napoleon and other military princes have crowned themselves; and he, like the Caesars, wore a wreath that was, after all, made of green leaves or vegetation. There can be other historical parallels, of course, if the reader is ready to look at such a hat without judgement.

The people going to church certainly looked at it; but they did not look at it without judgement. They followed the Colonel as he walked almost cheerfully up the road, with feelings that no philosophy could for the moment describe. There seemed to be nothing to be said, except that one of the most respectable and respected of their neighbours, one who might even be called in a quiet way an example of good manners if not a leader of fashion, was walking solemnly up to church with a cabbage on the top of his head.

There was indeed no general action to meet the crisis. In their world a crowd could not gather to shout or to attack someone. No rotten eggs could be collected from their tidy breakfast-tables; and they were not those people who could throw old cabbage leaves at the cabbage. Each of these men lived alone and they could not create an angry crowd. For miles around there were no public houses[4]4

Public houses = pubs (пабы).

[Закрыть] and no public opinion.

When the Colonel approached the church porch and prepared respectfully to remove his vegetarian hat, he was greeted in a tone a little more cheerful than the everyday friendly manners of his neighbours. He responded to the greeting without embarrassment, and paused for a moment when the man who had spoken to him decided to continue speeking. This was a young doctor named Horace Hunter, tall, handsomely dressed, and confident in manners. Though his face was rather ordinary and his hair rather red, he was considered to have a certain charm.

“Good morning, Colonel,” said the doctor more loudly than usual, “what a f… what a fine day it is.”

Stars turned from their courses like comets, so to speak, and the world moved towards wilder variants, at that crucial moment when Dr. Hunter corrected himself and said, “What a fine day!” instead of “What a funny hat!” The reason why he corrected himself, a true picture of what passed through his mind might sound rather exotic in itself. It would be less than enough to say he did so because of a long grey car waiting outside the Colonel’s house. It might not be a complete explanation to say it was because of a lady walking on stilts at a garden party. It might still not be clear, even if we said that it had something to do with a nickname; nevertheless all these things mixed together in the medical gentleman’s mind when he made his decision. Above all, it might or might not be sufficient explanation to say that Horace Hunter was a very ambitious young man, that the ring in his voice and the confidence in his manner came from a very simple resolution to rise in the world.

He liked to be seen talking so confidently to Colonel Crane on that Sunday parade. Crane was comparatively poor, but he knew People. And people who knew People knew what People were doing now; while people who didn’t know People could only wonder what in the world People would do next. A lady who came with the Duchess when she opened the local market had nodded to Crane and said, “Hello, Stork,” and the doctor had decided that it was a sort of family joke and not a small ornithological mistake. And it was the Duchess who had started all that racing on stilts, which the Vernon-Smiths had introduced at their house. But it would have been devilish awkward not to know what Mrs. Vernon-Smith meant when she said, “Of course you stilt.” You never knew what they would start next. It was strange to imagine that he would ever begin to see vegetable hats here and there, but you never could tell. His first medical impulse was to add a straitjacket to the Colonel’s unusual costume. But Crane did not look like a madman, and certainly did not look like a man who was joking. He took it quite naturally. And one thing was certain:if it really was the latest fashion thing, the doctor must take it as naturally as the Colonel did. So he said it was a fine day, and was very happy to learn that there was no disagreement on that question.

The doctor’s dilemma, if we may use the phrase, was the whole neighbourhood’s dilemma. The doctor’s decision was also the whole neighbourhood’s decision. It was not so much that most of the good people there shared Hunter’s serious social ambitions, but rather that negative and cautious decisions were natural for them. They did not want other people to bother them about how they lived; and they followed the same principle by not bothering others. They also felt that the polite and respectable military gentleman would not be a very easy person to bother. The result was that the Colonel carried his monstrous green hat about the streets of that suburb for nearly a week, and nobody ever mentioned the subject to him. It was about the end of that time (while the doctor had been scanning the horizon for aristocrats crowned with cabbage, and, not seeing any, was collecting his courage to speak) that the final interruption came, and with the interruption the explanation.

The Colonel looked like he had completely forgotten all about the hat. He took it off and put it on like any other hat; he hung it on the hat-peg in his narrow front hall where there was nothing else but his sword and an old brown map of the seventeenth century. He gave it to Archer when that loyal man insisted on his official right to hold it. Archer did not insist on his official right to brush it, because he was afraid it could fall to pieces; but he occasionally gave it a cautious shake, accompanied by a look of restrained dislike. But the Colonel himself never showed any signs of either liking or disliking it. The unconventional thing had already become one of his conventions – the conventions which he never thought about enough to break. So it is probable that what at last happened was as much of a surprise to him as to anybody. Anyway, the explanation, or explosion, came in the following way.

Mr. Vernon-Smith was a small, neat gentleman with a big nose, dark moustache, and dark eyes with a constant expression of anxiety, though nobody knew what he was so anxious about in his very solid social life. He was a friend of Dr. Hunter; you could almost say a humble friend. He had the negative snobbishness that could only admire the positive and progressive snobbishness of that social figure. A man like Dr. Hunter likes to have a man like Mr. Smith, because he can pose as a perfect man of the world before him. What is more extraordinary is that a man like Mr. Smith really likes to have a man like Dr. Hunter to pose and to show his superiority. Anyhow, at one moment Vernon-Smith decided to hint that the new hat of his neighbour Crane did not look like it was from a fashion magazine. And Dr. Hunter, bursting with his secrets, called this idea stupid and made jokes about it. With calculated, confident gestures, with large phrases full of allusions, he left on his friend’s mind the impression that the whole social world would be destroyed, if anyone said a word on such a delicate topic. Mr. Vernon-Smith formed a general idea that the Colonel would explode with a loud bang at the slightest hint on vegetables, or any word which sounded just a little bit like ‘hat’. As usually happens in such cases, the words he was forbidden to say repeated themselves constantly in his mind with the rhythm of his pulse. At the moment he wanted to call all houses hats and all visitors vegetables.

When Crane came out of his front gate that morning he found his neighbour Vernon-Smith standing outside, between a tree and a lamp-post, talking to a young lady, a distant cousin of his family. This girl was an art student – a little too independent for the standards of this neighbourhood. Her brown hair was cut very short, and the Colonel did not admire short haircuts. On the other hand, she had a rather attractive face, with honest brown eyes a little too wide apart, which diminished the impression of beauty but increased the impression of honesty. She also had a very fresh and natural voice, and the Colonel had often heard it calling out scores at tennis on the other side of the garden wall. In some way it made him feel old; at least, he was not sure whether he felt older than he was, or younger than he was supposed to be. It was not until they met under the lamp-post that he knew her name was Audrey Smith; and he was thankful for the simple short name. Mr. Vernon-Smith presented her, and very nearly said:“May I introduce my cabbage?” instead of “my cousin.”

The Colonel, without a change in his intonation, said it was a fine day. And his neighbour, happy to escape from a very difficult situation, continued the conversation cheerfully. His manner, like when he came to local meetings and committees, was at once hesitating and confident.

“This young lady is going into Art,” he said; “a poor prospect, isn’t it? I expect we will see her drawing in chalk on the pavement and expecting us to throw a penny into the – into a tray, or something.” Here he escaped from another danger. “But of course, she thinks she’s going to be a Royal Academician[5]5

Royal Academician – член Королевской академии изящных искусств.

[Закрыть].”

“I hope not,” said the young woman hotly. “Pavement artists are much more honest than most of the Royal Academicians.”

“I wish those friends of yours didn’t give you such revolutionary ideas,” said Mr. Vernon-Smith. “My cousin knows the most dreadful eccentrics, vegetarians and – mad Socialists.” He decided to say it, feeling that vegetarians were not quite the same as vegetables; and he felt sure the Colonel would share his horror of Socialists.

“People who want to be equal, and all that. What I say is – we’re not equal and we never can be. As I always say to Audrey – if all the property were divided tomorrow, it would go back into the same hands the next day. It’s a law of nature, and if a man thinks he can get round a law of nature, why, he’s talking through his – I mean, he’s as mad as a – “

Trying to escape from the image in his head, he was searching madly in his mind for the alternative of a March hare[6]6

Мистер Вернон-Смит пытается избежать английских поговорок, в которых упоминаются шляпы. To talk through one’s hat – «говорить через шляпу», т. е. говорить с уверенным видом о предмете, о котором человек не имеет никакого понятия. As mad as a hatter – «безумен как шляпник», т. е. совершенно сошёл с ума (вспомним «Алису в стране чудес» Л. Кэрролла). Спасти мистера Вернон-Смита могла бы поговорка as mad as a March hare – «безумен как мартовский заяц» (тоже персонаж «Алисы»).

[Закрыть]. But before he could find it, the girl had cut in and completed his sentence. She smiled calmly, and said in her clear and ringing tones:

“As mad as Colonel Crane’s hatter.”

It is not unjust to Mr. Vernon-Smith to say that he ran as from a dynamite explosion. It would be unjust to say that he left a lady in distress, because she did not look in the least like a distressed lady, and he himself was a very distressed gentleman. He tried to ask her to go indoors, and then vanished there himself with a random apology. But the other two took no notice of him; they continued to confront each other, and both were smiling.

“I think you must be the bravest man in England,” she said. “I don’t mean anything about the war, or your medal and all that; I mean about this. Oh, yes, I know a little about this, but there’s one thing I don’t know. Why do you do it?”

“I think it is you who are the bravest woman in England,” he answered, “or, at any rate, the bravest person in these parts. I’ve walked about this town for a week, feeling like the last fool on Earth, and expecting somebody to say something. And not a soul has said a word. They all seem to be afraid of saying the wrong thing.”

“I think they’re deadly,” said Miss Smith. “And if they don’t have cabbages for hats, it’s only because they have turnips for heads.”

“No,” said the Colonel gently, “I have many generous and friendly neighbours here, including your cousin. Believe me, there is a reason why people have conventions, and the world is wiser than you know. You are too young not to be intolerant. But I can see you’ve got the fighting spirit; that is the best part of youth and intolerance.”

“You see, I can’t keep calm when they say all these polished vulgarities about everything – look at what he said about Socialism.” answered the girl.

“It was a little superficial,” said Crane with a smile.

“And that,” she concluded, “is why I admire your hat, though I don’t know why you wear it.”

This trivial conversation had a curious effect on the Colonel. There went with it a sort of warmth and a sense of crisis that he had not known since the war. A sudden purpose formed itself in his mind, and he spoke like one stepping across a border.

“Miss Smith,” he said, “I wonder if I might ask you to pay me a bigger compliment. It may be unconventional, but I believe you do not insist on these conventions. An old friend of mine will be visiting me shortly, to finish the rather unusual business or ceremonial of which by chance you have seen a part. If you would do me the honour to have lunch with me tomorrow at half-past one, the true story of the cabbage awaits you. I promise that you will hear the real reason. I might even say I promise you will SEE the real reason.”

“Oh, of course I will,” said the unconventional one cheerfully. “Thanks awfully.”

The Colonel took an intense interest in the preparations for lunch next day. With surprise he found himself not only interested, but excited. Like many of his type, he took a pleasure in doing such things well, and knew his way about in wine and cookery. But that would not alone explain his pleasure. Because he knew that young women generally know very little about wine, and emancipated young women probably least of all. And though he wanted the cookery to be good, he knew that one part of it would appear rather fantastic. Again, he was a good-natured gentleman who wanted young people to enjoy a lunch party, as he would have wanted a child to enjoy a Christmas tree. But there seemed no reason why he should have a sort of happy insomnia, like a child on Christmas Eve[7]7

Christmas Eve – канун Рождества, на следующее утро детей ждут подарки.

[Закрыть]. There was really no excuse for his walking up and down the garden with his cigar, smoking furiously almost till the morning. Because while he looked at the purple irises and the grey pool in the moonshine, something in his feelings moved as if from the one end to the other; he had a new and unexpected reaction. For the first time he really hated the masquerade he had put himself through. He wished he could smash the cabbage as he had smashed the top-hat. He was little more than forty years old, but he suddenly felt the monstrous and solemn vanity of a young man growing inside him. Sometimes he looked up at house next door, dark against the moonrise, and thought he heard quiet voices in it, and something like a laugh.

The visitor who came to the Colonel next morning may have been an old friend, but he certainly had a very different personality. He was a very absent-minded, rather untidy man in a shabby suit; he had a long head with straight hair of the dark red colour, one or two bits of which stood on end however he brushed it. His face was long and clean-shaven and a little fuller around the jaw and chin, which he usually put down and settled firmly into his cravat.

His name was Hood, and he was a lawyer, though he had not come to the Colonel on strictly legal business. Anyhow, he exchanged greetings with Crane with a quiet warmth and satisfaction, smiled at the old servant as if he were an old joke, and showed every sign of an appetite for his lunch.

The appointed day was unusually warm and bright, and everything in the garden seemed to glitter; the goblin god of the Oceania seemed really to grin; and the scarecrow really to have a new hat. The irises round the pool were swinging and flapping in a light wind; and he remembered they were called “flags” and thought of purple banners going into battle.

She had come suddenly round the corner of the house. Her dress was of a dark but fresh blue colour, of a very simple form, but not too artistic. And in the morning light she looked less like a schoolgirl and more like a serious woman of twenty-five or thirty; a little older and a great deal more interesting. And something in this morning seriousness increased the reaction of the night before. One single wave of relief went through Crane to think that at least his terrible green hat was gone and finished with for ever. He had worn it for a week without caring one bit for anybody’s opinion; but during that ten minutes’ trivial conversation under the lamp-post, he felt as if he had suddenly grown donkey’s ears in the street.

Because of the sunny weather he prepared a little table for three in a sort of veranda open to the garden. When the three sat down to it, he looked across at the lady and said:

“I fear I’m going to look like an eccentric; one of those eccentrics your cousin disapproves of, Miss Smith. I hope it won’t spoil this little lunch for anybody, but I am going to have a vegetarian meal.”

“Are you?” she said. “I would never have said you looked like a vegetarian.”

“Just lately I have only looked like a fool,” he said calmly; “but I think I’d sooner look a fool than a vegetarian in the ordinary way. This is rather a special occasion. Perhaps my friend Hood had better begin; it’s really his story more than mine.”

“My name is Robert Owen Hood,” said that gentleman, rather sarcastically.

“That’s how improbable memories often begin; but the only point now is that my old friend here insulted me horribly by calling me Robin Hood.”

“I would have called it a compliment,” answered Audrey Smith. “Buy why did he call you Robin Hood?”

“Because I used the long bow[8]8

Because I used the long bow – игра слов; long bow – длинный английский лук, которым, согласно балладам, пользовались Робин Гуд и его товарищи; одновременно с этим, Худ имеет в виду свою медлительность (ср. русскую поговорку «долго запрягает»).

[Закрыть],” said the lawyer.

“But to do you justice,” said the Colonel, “it seems that you hit the bull’s eye.[9]9

To hit the bull’s eye – англ. поговорка:«попасть в глаз быка», т. е. попасть в яблочко, попасть в десятку.

[Закрыть]”

While he spoke

Archer came in with a dish which he placed before his master. He had already served the others with the earlier meals, but he carried this one with the pomp of one bringing the boar’s head at Christmas[10]10

The boar’s head – кабанья голова, традиционное рождественское угощение в Британии.

[Закрыть]. It consisted of a plain boiled cabbage.

“I was challenged to do something,” continued Hood, “which my friend here declared to be impossible. In fact, any sane man would have declared it to be impossible. But I did it all the same. Only my friend, in the heat of rejecting and mocking the idea, used an expression he didn’t think about. I might almost say he made a rash vow[11]11

Made a rash vow – дал поспешный обет.

[Закрыть].”

“My exact words were,” said Colonel Crane solemnly, “‘If you can do that, I’ll eat my hat.’”

He leaned forward thoughtfully and began to eat it. Then he continued in the same meditative way:

“You see, all rash vows are literal or nothing. There might be a debate about the logical and literary way in which my friend Hood fulfilled HIS rash vow. But I accepted it as a challenge in the same pedantic sort of way. It wasn’t possible to eat any hat that I wore. But it could be possible to wear a hat that I could eat. Parts of dress could hardly be used for diet; but parts of diet could really be used for dress. It seemed to me that it could become my hat, if I wore it systematically as a hat and had no other, putting up with all the disadvantages. Making a fool of myself was the fair price to be paid for the vow or bet; because you should always lose something on a bet.”

And he rose from the table with a gesture of apology.

The girl stood up. “I think it’s perfectly splendid,” she said. “It’s as wild as one of those stories about looking for the Holy Grail.[12]12

Holy Grail – Святой Грааль, в поисках которого рыцари короля Артура совершили множество славных подвигов.

[Закрыть]”

The lawyer also had risen, rather quickly, and stood touching his long chin with his thumb and looking at his old friend under bent brows in a rather meditative manner.

“Well, you’ve made me a witness all right,” he said, “and now, with the permission of the court, I’ll leave the witness-box. I’m afraid I must be going. I’ve got important business at home. Good-bye, Miss Smith.”

The girl answered a little mechanically; and Crane seemed to recover from a similar trance, when he stepped after the retreating figure of his friend.

“I say, Owen,” he said quickly, “I’m sorry you’re leaving so early. Do you really have to go?”

“Yes,” replied Owen Hood gravely. “My private affairs are quite real and practical, I assure you.” His grave mouth showed some signs of a smile at the corners when he added:“The truth is, I don’t think I mentioned it, but I’m thinking of getting married.”

“Married!” repeated the Colonel, as if struck by a lightning.

“Thanks for your compliments and congratulations, old fellow,” said the satiric Mr. Hood. “Yes, it’s all been thought through. I’ve even decided who I am going to marry. She knows about it herself. She has been warned.”

“I am really sorry,” said the Colonel in great distress, “of course I congratulate you from my heart; and her even more so. Of course I’m very happy to hear it. The truth is, I was surprised… not so much in that way…”

“Not so much in what way?” asked Hood. “I suppose you mean some would say I was on the way to be an old bachelor. But I’ve discovered it isn’t half so much a question of years as of habits. Men like me get elderly more by choice than chance; and there’s much more choice and less chance in life than your modern fatalists believe. For such people fatalism changes even chronology. They’re not unmarried because they’re old. They’re old because they’re unmarried.”

Внимание! Это не конец книги.

Если начало книги вам понравилось, то полную версию можно приобрести у нашего партнёра - распространителя легального контента. Поддержите автора!